Traditionally, I use this space to write something political. It’s part of my brand, and I’ve been assured by several editors that personal branding is indispensable to the modern writer. I’ve got to admit, though, that I’m not really feeling it this year. I thought the Capitol rioters were a bunch of yahoos, and therefore no more interesting than the next gang of hooligans. They had an opportunity to do something really destructive, and therefore scarily consequential, and they blew it; as far as I’m concerned, that’s the entirety of the story. They’re never going to get a wide-open shot like that again, thank goodness. QAnon is incredibly stupid, and its proliferation has ruined conspiracy theory, which used to be shadowy and spy-like, and now just feels like empty calories for bored senior citizens. Trump’s board position has been deteriorating from the moment he caught the coronavirus, and I see no reason why that will change. There’s a very good chance that American politics will go back to being dull, a niche interest for nerds, and this, I believe, would be a welcome development.

But I do have one politics-adjacent thing I’d like to get off my chest, and I’m going to do it right here. Every time a newscaster, or even a peer, places an American politician on a left-right spectrum, I throw up a little in my mouth. It’s not that I oppose the ordinal classification of human beings who are straining to be two-dimensional; that’s fine, honestly. But as people who take discourse and syntax seriously, I think we have to be more scrupulous about the terms we use and their accidental effects.

For starters, think about the hand you’re favoring right now, for the serious business of scrolling through this message or paging through your phone. If you’re like ninety per cent of humanity, you’re a righty. Outside of championship bullpens, those who favor their left hand are pretty rare. When we call ourselves leftists, on some unconscious level, we’re drawing on this association: we’re already accepting that we’re a minority, and that we’ll always be outnumbered and outvoted by those boxers who lead with their right. Then there are the dictionary definitions of the words: right is synonymous with correct, or proper, or squared away. We also talk about rights, and these are good things, natural things we’ve all fought for and like to defend. The right has pleasant connotations.

By contrast, there’s the left behind, warmed-over leftovers, the left hand of darkness, garbage left in the gutter after the street sweeper comes by. As every beginning etymologist knows, sinister is Latin for left. Gauche is French for left. You catch my drift. Left equals bad, and always has. It bugs the heck out of me that people who generally argue for a fair and egalitarian distribution of power (not that this has ever exactly described me, but I do have my sympathies) have embraced this particular bit of anti-marketing.

Mostly, I hate the imposition of European nomenclature on an American society where it has never fit. Many so-called European leftists have a misty vision of the French Revolution and the Left Bank and the revolutions of 1848; it’s all hooey and less than half understood, but it’s part of their heritage, so you can’t begrudge them their terminology. The vast majority of Americans couldn’t tell you much about any of that. There are enough empty terms in American public life; we don’t need to muddy the waters with additional meaningless descriptors. Our politics aren’t rocket science. In America, we have Democrats and we have Republicans. If you can’t figure out what that means by now, you probably shouldn’t be talking about politics at all.

Back to more pleasant subjects, such as:

Single of the Year

- 1. The Beths – “Jump Rope Gazers”

- 2. Natalia Lafourcade – “Una Vida”

- 3. Dua Lipa – “Break My Heart”

- 4. Sotomayor – “Menéate Pa’ Mí”

- 5. Poppy – “I Disagree”

- 6. Troye Sivan – “Rager Teenager”

- 7. Francisca Valenzuela – “Tómame”

- 8. Haim – “The Steps”

- 9. The Strokes – “Brooklyn Bridge To Chorus”

- 10. Bruce Springsteen – “Ghosts”

- 11. Lido Pimienta – “Eso Que Tú Haces”

- 12. The Weeknd – “In Your Eyes”

- 13. Poppy – “Concrete”

- 14. Samia – “Big Wheel”

- 15. Róisín Murphy – “Narcissus”

- 16. Porridge Radio – “Lilac”

- 17. Dua Lipa – “Levitating”

- 18. Felivand – “Trajectory”

- 19. Kacy Hill & Francis And The Lights – “I Believe In You”

- 20. Buscabulla – “Vamanó”

Best Album Title

Kacy Hill’s Is It Selfish If We Talk About Me Again. I also want to acknowledge the accidental relevance of Hotspot. The Pet Shop Boys could be referring to a trendy nightclub, an erogenous zone, or a placed where armed conflict or infectious disease is breaking out. Tennant and Lowe always know where we’re headed.

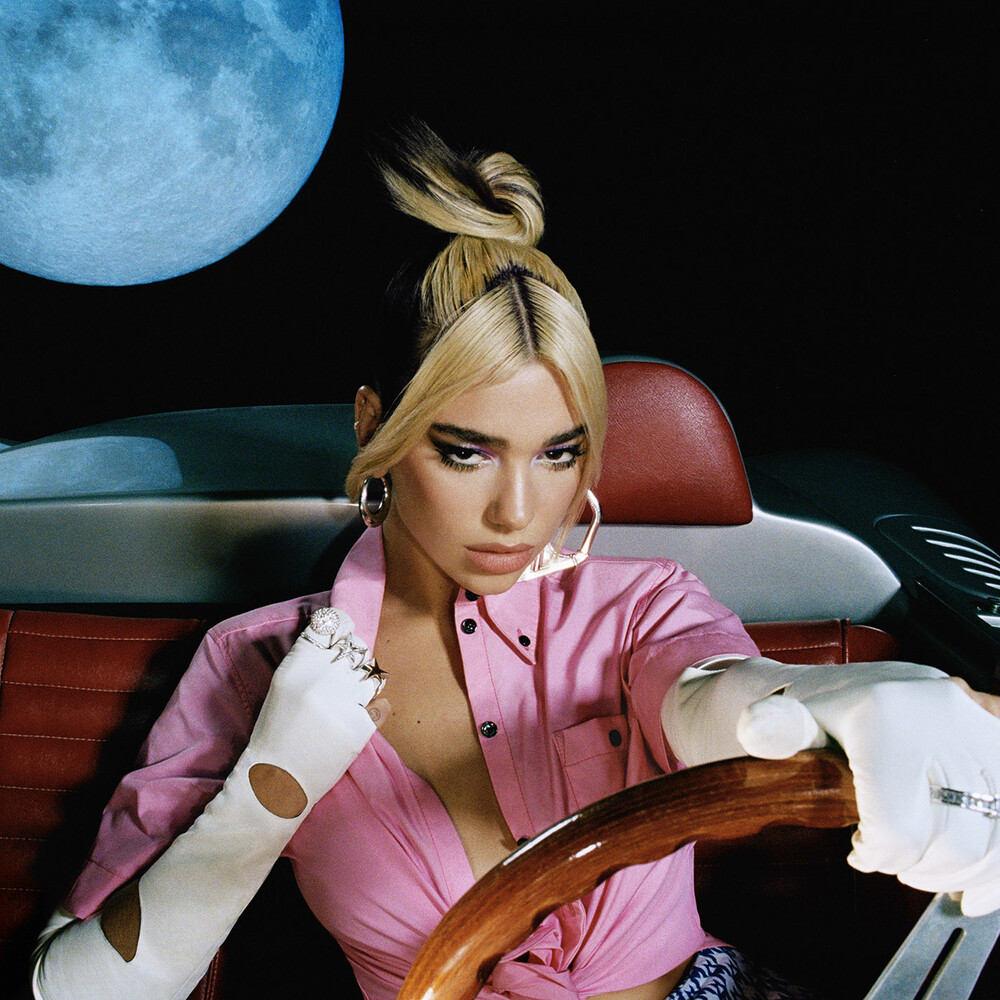

Best Album Cover

Check out Dua Lipa in the car above, eyes down, big moon egging her on. You know it’s a summer night, because he shirt is unbuttoned and provocatively tied, and the convertible top is down. She’s put some thought into the ensemble: the lipstick, the big earrings, the white gloves with the rings over the covered fingers. But what’s she thinking? She’s probably heading out – she’s a little too smartly attired and unsmudged to be returning from the club. It’s pretty clear that she’s looking for adventure, but there’s something hesitant and contemplative about her expression, too. Superficially, she’s driving a signifier of the past (the vintage auto) into the future, symbolized by the road ahead. Her determination is clear, but she doesn’t exactly look unswervable. Is she really the “female Alpha” she tells us she is? Or do we just have a tricky time recognizing what that might look like?

Best Liner Notes And Packaging

Straight across Folklore and Evermore: the photos, the clothing, the layout, the now-customary from-me-to-you notes from the star, the woodsy, throwback font choice. Cabins in the woods are pretty dull places. There’s nothing to do in there but sweat the details, and whittle away.

Most Welcome Surprise

Because his imagination is vast and insular, and his capacity for self-amusement is enormous, Paul McCartney was a good quarantine companion. But I didn’t expect him me with a new release that’s better than anything he’s done since Chaos And Creation In The Backyard. At 80, his voice is shot, but he still knows how to use it to generate some beauty and mystery. “Deep Deep Feeling” was one of the year’s weirdest and most profound songs, and it came from a guy who is far weirder and more profound than his jovial public image might lead the uninitiated to believe.

Biggest Disappointment

Ice Cube. That hurt a thousand times more than Kanye, and a million times more than Lil Wayne, who was clearly just sniffing out a pardon. I don’t care how much money he lost on that stupid basketball league; there’s no excuse for cozying up to wannabe oligarchs. By getting in bed with the authorities, Cube blew a hole in the greatest dis track ever recorded, which turned on the line that emcee felt the need to reiterate for emphasis: I never have dinner with the President. Remember: he wasn’t just running down Eazy-E. He was making a declaration of autonomy meant to apply to all artists and all independents. It doesn’t matter what people in power promise you; you don’t need it, and you certainly don’t need them. You stand on your own and you never compromise. And yes, it’s pathetic that a weenie like me has to explain what it means to be gangsta, but we can’t depend on Cube to do it anymore. He abdicated that responsibility entirely. If I look stupid doing so, blame him: he drove me to it. Oh, and I never have dinner with the President. No matter who that President might be.

Song of the Year

Album That Opens Most Strongly

I Disagree covers about nine thousand genres in its first eight minutes. Poppy, who didn’t demonstrate much flexibility on the microphone on her prior albums, never makes an errant step. Touring is an incredible thing. It’s still the quickest way to turn a lump of coal into a diamond.

Album That Closes Most Strongly

Hit To Hit, by 2nd Grade. In accordance with college rock tradition, the final fifth of the album contains the wistful reflections, the eager anticipations of summers to come, and some casual (but genuine) observational poetry. The members of Camper Van Beethoven would nod in recognition.

Best singing

Best rapping

Megan Thee Stallion. This was the easiest question on the Poll for me. I continue to be astonished by the number of rhyme styles and flows she’s able to yoke together on Good News: Dirty Southern, Golden Age NYC, quick-spitting Midwestern, classic Southern Californian, even a little hyphy for good measure. But no matter how deep into the crates she digs, she remains identifiably Houstonian, and thoroughly contemporary, too. Her broad record collection, her deep connection to history, her tart tongue, her charisma, her battle-of-the-sexes subject matter, and her taste for violence all remind me of another favorite Texan vocalist of mine: Miranda Lambert. Country and hip-hop remain the two faces of the same golden American coin.

Best vocal harmonies

“Marjorie,” from Evermore.

Best bass playing

Robert Earl Thomas of Widowspeak, and the cast of thousands who cut those tremendous, disco-ready bass parts on Future Nostalgia.

Best live drumming

I want to vote for Mighty Max, but I can’t front: the answer is Matt Uychich of The Front Bottoms. At least I’m keeping it Jersey.

Best drum and instrument programming

Kelly Lee Owens

Best synth playing/programming

Kevin McDowell of the Australian prog-jazz group Mildlife. Everybody in that band is a genuine virtuoso.

Best piano, organ, or electric piano playing

Roy Bittan, over all the imitators.

Best guitar playing

Charlie Hunter on Lo Sagrado, with special recognition given to Devon Williams for his gorgeous textures on A Tear In The Fabric. That would have been a good answer for Best Album Title and Best Album Cover, too. It’s just so understated that it rarely comes to mind, but when it’s on, it’s a delight.

Best instrumental solo

Poppy’s guitarist on “Don’t Go Outside” and “Bloodmoney”. No instrumental credits in the liner notes, alas.

Best instrumentalist

Andy Shauf played everything on The Neon Skyline, including more clarinet than I’ve heard on a record since the heyday of chamber pop.

Best production

Kenny Segal. See yesterday’s essay for further discussion. My single favorite production of the year was “Tis The Damn Season”, from Evermore. That’s the one where the icicle-dripping sound that the National dudes developed for Taylor Swift meets the storytelling in the most satisfying, totalizing, vision-generating way. I can see the frost clouding the windows, and the white steeple of the Presbyterian Church across the street, and smell the wood smoke. Just thinking about that song makes me reach for a blanket. Job well done, dudes from the National.

Best arrangements

Sevdaliza’s Shabrang. When I wrote in the Abstract that Phil Collins had invented trip-hop with “In The Air Tonight”, I was just kidding. Sorta.

Best songwriting

I’m not sure anybody moved melodies across chords with the grace and majesty of Maria McKee. You probably didn’t notice, and that’s because that record is so bombastic that you blushed. Yes, you blushed so hard that it was audible, and palpable, and your burning cheeks set the piano ablaze. If you can fight through that initial embarrassment, songwriting riches await. I promise.

P.F. Rizzuto award for best lyrics over the course of an album

Best lyrics on an individual song

I’ve come to see Lupe Fiasco’s House as a magnificent tightrope walk: a quick but oh-so-potent album about how artists might possibly navigate capitalism and oppression and keep their creative spirits intact. Lupe neither indulges in the upwardly mobile materialism that defines so much of g-rap, nor does he cast stones at it the way, say, Homeboy Sandman does on Don’t Feed The Monster. Instead he looks to carve out spaces within consumer culture for people with creative spirits to operate. It’s the same affirmative impulse that’s always prompted him to write in a laudatory fashion about various subcultures – i.e., “Kick Push” – and upon reflection, I think it’s kinda beautiful, and very, very hip-hop. He’s not stupid about it – he knows how predatory the world is. He sees all the dangers. But his advice to the aspiring model on “SLEDOM” is sincere, and his examination of the dynamics of the sneaker-drop line on “SHOES” is an inspiring and necessary counterpoint to Ajai. Thanks, Lupe, for reminding me again that it’s all one big and continuous argument, and the only really irresponsible thing you can do is stop speaking.

Band of the Year

Best live performance you saw in 2020, including, alas, YouTube clips

Here’s Roger Waters and his crew doing “Two Suns In The Sunset”, the nuclear war number that concluded his tenure with Pink Floyd, via teleconference.

Best music video

- 1. Drake – “Toosie Slide”

- 2. Tame Impala – “Lost In Yesterday”

- 3. Fiona Apple – “Shameika”

- 4. Felivand – “Trajectory”

- 5. Sotomayor – “Menéate Pa’ Mí”

- 6. The Orielles – “Come Down On Jupiter”

- 7. Ximena Sariñana – “Una Vez Más”

- 8. Dua Lipa – “Physical”

- 9. Jennifer Lopez & Maluma – “Pa’ Ti”

- 10. Fontaines D.C. – “A Hero’s Death”

A word about the amazing clip for the “Toosie Slide”

First we’re shown Toronto, deserted. Drake lets us know that it’s 10:20 p.m.; under normal conditions, these streets would be choked with cars and pedestrians. For a moment, you think it’s a special effect. Then the moment passes, and you remember. This isn’t sci-fi: this is a real life disaster we’re living through, one that’s still unfolding all around us, outcome indeterminate. Then Drake takes you inside his mansion. He’s masked, dressed in a hood and a camouflage jacket, and the contrast between his attire and the sterile nouveau riche opulence of the interior of his house is striking. Everything looks fragile, smash-and-grab-able – bottles of expensive whiskey, designer lightbulbs in gaudy chandeliers, trophies behind glass cases. You know Drake; you know he’s won all of those awards; you may have even watched him receive them. Furthermore, you know why he’s masked – it’s the same reason why you’re masked. Nevertheless, you can’t shake the sense that you’re watching a home invasion. He’s daring you to imaginatively dispossess him – challenging you to accept him as the rightful owner of all of this grotesque and conspicuous wealth. He asks you: why do you see me as an interloper? Have I not done enough for you to prove to you that I belong? Is that not my profile on that platinum disc of Nothing Was The Same on the wall? When he does the ridiculous TikTok dance between two KAWS statues, on the marble floor of his foyer, decked out with LEDs and the alarm system flashing in the distance, it’s all so incongruous that the pathos of the present moment comes crashing in on you like a battering ram. Even the fireworks display in the backyard is no release, because he’s got no one to share it with. Lonesome cousin Drake, thematizing his solitude and ostracism once again, chilling you to the bone with an ice cold clip, shot on a cold night in a cold city, in the midst of a cold, cold time.

Most romantic song

Elzhi’s “Ferndale”

Funniest song

Most frightening song

I Disagree still shows up in my nightmares, “Bite Your Own Teeth” in particular. Poppy’s entire body of work — with and without Titanic Sinclair — is one ongoing horror movie. True, sometimes it’s funny as hell. Good horror movies often are.

Most moving song

Probably “August”, all things considered.

Sexiest song

Francisca Valenzuela’s “Tómame”. “Ya No Se Trata De Ti,”, too. Then there’s Natalia Lafourcade’s cover of “Ya No Vivo Por Vivir”, and her gorgeous “Mi Religión” clip. What can I say?, I think Español is kinda sexy.

Most inspiring song

Paul McCartney’s “Seize The Day” and “When Winter Comes”.

Meanest song

I was going to give this one to Morrissey, since he sees no point in being nice, and boy howdy does he ever act out those words. But Of Montreal‘s “Don’t Let Me Die In America” is such an unrelenting sneer directed at the unfashionable quadrants of the country that it’s liable to kick off another Capitol riot. Not that I don’t agree with Kevin, and rather deeply at that. But then I’m an elitist scumbag, too.

Saddest song

Homeboy Sandman’s “Alone Again” and Open Mike Eagle’s “The Black Mirror Episode,” and for the same damn reason, because they’re the same damn song. Neil Sedaka said it in ’62: breaking up is hard to do.

Most notable cover version or interpretation

Baila Esta Cumbia, Ángela Aguilar‘s EP-length tribute to Selena.

Rookie of the Year

Best guest appearance or feature

I’m impressed by Taylor Swift’s ability to squeeze value out of all of her dicy collaborators. She managed to get two semi-coherent verses out of Justin Vernon, which something I didn’t think was possible once. I thought he was completely committed to the garbled robot act. It helps that they’re all Springsteen fans/imitators to one degree or another: they have that appreciation of “Two Faces Have I” and “Tougher Than The Rest” in common. They knew what they were shooting for. But mostly I just think that the presence of an intelligent and talented woman tends to make guys get their shit together. I know it’s the only thing that ever works for me.

2020 album you listened to the most

Song For Our Daughter

Album that wore out the quickest

Eternal Atake by Lil Uzi Vert

Best sequenced album

The Neon Skyline

Most convincing historical recreation

Honestly, it’s the Hot Country Knights. It’s a parody act, but they really do nail the sound and feel of ’90s country.

Crummy album you listened to a lot anyway

Khruangbin‘s Mordechai. That bass player is really good. It’s empty calories otherwise: junk food in the international terminal at JFK.

Album that felt the most like an obligation to get through and enjoy

Caroline Rose‘s new one. I loved Loner so much – it was #5 for me in 2018 – and I kept searching, hard, for the through-story on Superstar that I was told was there. I got lost in the synthesizer overdubs every time. It didn’t seem like Caroline was the sort of artist who’d fall into the mushrock trap, but fall she did, and there’s only so much fighting the listener can do to pull a past favorite out of the tar pit.

Artist you don’t know, but you know you should

Chloe x Halle

Album that sounded like it was a chore to make

Album that sounded like it was the most fun to make

Man, I wish I knew what this album was about

I don’t even know what language Idd Aziz is singing in on Umoja, but I definitely comprehend that organ sound.

Most consistent album

Mission Bells by the Proper Ornaments. Forty minutes of pure, uninterrupted lite-psychedelic swirl.

Most inconsistent album

Hey Clockface. After a pair of late career triumphs, Elvis gets scattershot: a few spoken word pieces, a couple of scruffy rave-ups, some old-man jazz, and a couple of killer ballads (“We Are All Cowards Now”, “The Whirlwind”) that are worth the price of the album. Also, I love “Hetty O’Hara Confidential”, a story about the demise of a gossip columnist that could only have been written by Elvis, and which reminds us that an aging king still beats the heck out of a callow knave.

Album that should have been shorter

Teyana Taylor’s interminable The Album.

Project that should have been longer

Troye Sivan‘s In A Dream. It works well as a brief encounter, but Troye is in the zone throughout, and it’s hard not to wish that he’d extended that studio stay and knocked out a few more tracks.

Album that turned out to be a hell of a lot better that you initially thought it was

Sin Miedo (Del Amor Y Otros Demonios). I wanted reggaeton fire from Kali Uchis, and was a little bummed out to get a bunch of zoned-out Bond themes instead. What I have come to realize is that they’re really good Bond themes. Impeccably sung, too. I’m going to be listening to this one all year, I’m sure.

Album that was the most fun to listen to

How could it be anything but Future Nostalgia?

Thing you feel cheapest about liking

American Love Story. Butch Walker, I love you forever, but everything about this rock opera of yours is beneath you – including the conciliatory politics. You don’t live in Rome, Georgia anymore for a good reason. You wanted to get the heck away from those people, and you were right to. You knew it then, and you still know it now: they’re not going to come to their senses.

Least believable perspective

Most alienating perspective over an album

Morrissey on I Am Not A Dog On A Chain, which isn’t to say that I don’t appreciate the album. I found some of those Smiths albums pretty alienating, too, wonderful as they are. I’m pretty sure I would’ve been in that disco he wanted to burn down.

Most sympathetic or likable perspective over an album

Peter Oren‘s The Greener Pasture. Peter understands that if you’re going to do a critique of social media, half-measures won’t do. You’ve got to go all the way with it.

Artist you respect, but don’t like

Album you learned the words or music to most quickly

In Sickness & In Flames

Album you regret giving the time of day to

Every time I listen to Grimes, I feel gross for days afterward. I warned you all years ago, people. Moreover, I warned you about Ariel Pink. Pay attention to me, and save yourself embarrassment down the line.

Young upstart who should be sent down to the minors for more seasoning

Hoary old bastard who should spare us all and retire

Worst song of the year

Worst singing

That falsetto outro on “House Of A Thousand Guitars” is pretty deadly. Sorry, Boss.

Worst rapping and Worst lyrics by a good lyricist who should have known better

Will Toledo on “Hollywood Makes Me Want To Puke”.

Worst lyrics, period

“Wine, Beer, Whisky” by Little Big Town. I call a moratorium on country artists directly addressing the corporate logos on alcohol bottles. It’s embarrassing for everybody. Jose Cuervo is not your friend, Ms. Fairchild.

Most unsexy person in pop music

Tekashi 6ix9ine has been trying very hard to win this category. I’m going to be a sport and give it to him.

Most overrated

Worst song on a good album

Margaret Glaspy’s “So Wrong It’s Right”. “Vicious”, though – that’s an absolute winner.

Most thoroughly botched production job

Helena Deland’s Something New. There are good songs under all that gook, I’m sure of it.

Song that would drive you craziest on infinite repeat

“Shit’s Crazy Out Here” by Bruce Hornsby

Good artists most in need of some fresh ideas

Song that got stuck in your head the most this year

“Menéate Pa’ Mí”. Poor Hilary.

Next artist to come out as a full blown reactionary

I’m guessing Mac DeMarco, or Post Malone.

Place the next pop music surge will come from

I’m just going to keep on saying Richmond, Virginia until it happens.

Will still be making good records in 2030

There’s no point in betting against Taylor Swift, is there?

Will be a one-hit wonder

Lil Mosey. Boy Pablo seems like a flash in the pan, too.

Biggest musical trend of 2021

Continued infiltration of metal into other musical styles, and convergence of metal with pop, folk, and some forms of hip-hop, too. Metal matches the national mood, I’ve noticed.

Best album of 2021?

I’m guessing that Kanye has one more classic in him.