Nobody wants to look old and in the way. This especially applies to critics, who need to keep up on trends or come off even more preposterous than they normally do, and musicians, who operate in an industry that puts a heavy premium on youth. Usually this isn’t much of a problem for me at this time of the year: there’s some kid’s-stuff mall emo I’m waving the flag for, or a 20-year-old rapper out of the Midwest with a mouthful of slang meant to confound mom and dad, or an indiepop project from adorable twee Scots who sound and behave so much like twelve-year-olds that they might as well be lined up for the recess bell. The world likes young people, the biz likes young people, I like young people, everything’s in bloom on the spring chicken farm.

But this year, my album list featured a septuagenarian coot in the top position, an even older grump at number six, and the grouchiest senior citizen in the entertainment industry at number eleven. What’s going on here? Have I finally capitulated to age and thrown in with the codgers? Or has the mask fallen, and am I now making my generational allegiances plain? Damn millennials with your cellular phones and your bit coins. Take those avocado toasts and shove ’em.

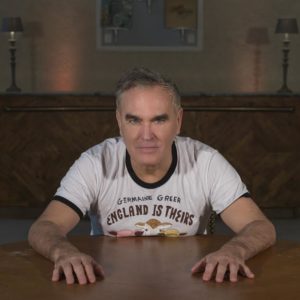

Probably not. In 2016 and 2017, we got a bunch of mea culpas from Baby Boomers; things, if you’ll notice, didn’t exactly turn out the way they were supposed to during the Summer of Love. They’re the Jerkiest Generation, and always have been, but at least they were kind enough to send their best poets to deliver the bad news. Message received; next year’s album list is virtually certain to skew toward the whippersnappers. But I’m glad things broke as they did, and not merely because I never miss an opportunity to tell the world what Roger Waters and Randy Newman (and, for that matter, Morrissey) have always meant to me. It also gives me an opportunity to clear up a few things up about my priorities — and there’s no safer place to do that than on a personal page that you’re only reading because you like me.

About five years ago, I was caught up in a long-running rock-crit debate between two warring ideological camps. On one side were so-called poptimists: critics, mostly younger, who believed that marginalized forms of popular music were just as worthy of critical scrutiny as those moldy old records designated classics by first-generation rock writers. They defended ephemerality as a virtue, argued that commercial performance was a legitimate barometer of merit in a capitalist industry, lionized fun and entertainment, and criticized their opponents for their implicit racism and sexism and insistence on evaluating everything by the standards set by late-’60s Beatles albums. Not everybody was trying to make Tommy, dammit, and it was unfair to demand a magnum opus out of every teenager with an MPC who probably just wanted to dance. On the other side of the debate were the rockists, largely older and largely male, who felt it was preposterous to stack, say, Britney Spears up against Bruce Springsteen. Any fool could see the difference in artistic merit between the two, and it was only doing readers a disservice to pretend that an equivalency existed. Rock, and pop, for that matter, had peaked around 1973, and everything has gone to hell in a handbasket since. Now I’m caricaturing the position, but not by very much. I’m also using the past tense, because the debate is more or less settled: the dust has cleared, and the poptimists have won. Major pop releases are now received with the seriousness that used to be reserved for rock records by canonical artists. It would be the rare critic indeed who’d argue that a new set from Rihanna, or Beyonce, didn’t deserve front-page treatment.

I love Beyonce, and Rihanna, and Katy Perry, and just about every other pop star you might like to name (hey, that new Camila Cabello album sounds pretty good…) Because I’ve been pretty loud about my appreciation for what they do, many readers have assumed that I pitch my tent among the poptimists, and have said so, in angry letters to the editor that I still have. Well, the nice ones called me a poptimist; the others used language that I won’t repeat here. Let’s just say they impugned a masculinity that I don’t exactly value in the first place. Many of these guys — and they were all guys, of course — were so vitriolic in their accusations that they were unable to see that I agreed with them far more than they thought I did. I just don’t condemn modern pop stars; I think they’ve managed to make some classic albums too. But my real, honest-to-god position is about as close to vulgar rockism as you’re likely to find from a critic who still cares, and very much, about contemporary music. I believe the classic period for pop and rock albums ran from 1967 to around 1974, and just about everything of merit since then has been attempts to recapture the glories of that period. The only difference between me and the worst of the rockists is that I’m still buying, and enjoying, new albums by the hundreds.

I do understand the sociopolitical problems with this, and I try to be sensitive to them. But just because something is problematic doesn’t mean it’s wrong — especially when everything we’ve ever learned about the history of artistic movements suggests that it’s right. Heydays exist. Those writing about other mediums aren’t shy about pointing them out. Elizabethan drama, Flemish portrait painting, Abstract Expressionism, bebop, Japanese bamboo art; heck, there are literary critics who’ll tell you that the novel went into aesthetic eclipse for decades in the mid Eighteenth century. There is a short period of groundbreaking and standard-setting, and then a much longer era of stasis, institutionalization, and decline. There oughtn’t to be anything controversial about pointing this out, just as there’s nothing outrageous about noticing and celebrating the great stuff that continues to get made after the classic period is over.

Mind you, none of this is nostalgia. I have no retrospective appreciation for the Vietnam era. That must have been an awful time to have been a young person. Advances in recording technology must have been, in that context, a very small consolation. But more consequential, I’d wager, than the advent of gazillion-tracking and the studio as an instrument and the Wall of Sound and all the rest of it was that it was then possible to get that technology into the hands of the right people. The business was, by modern standards, pretty small-time — it hadn’t consolidated yet. Nobody knew what the kids wanted; there was no good outline or target marketing, or, God forbid, any algorithm to predict audience response. Instead it was entirely reasonable, and economically defensible, to give money and resources to the big-nosed likes of Van Morrison or Randy Newman. A fully mature industry — one that operates confidently and efficiently — has neither interest in nor room for guys like that. They’re going to adhere to best practices, which will usually mean pleasing the crowd as expediently as possible. Since there are now instant methods of ascertaining crowd desire, their jobs are done for them.

And if you still don’t believe me, consider that we all watched this exact thing happen in hip-hop. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, the industry was shapeless, executives were tentative, and nobody had any idea what was going on or what was going to sell. This led to record deals and promotion for funny-looking, idiosyncratic, visionary artists who’d never, ever sniff major industry money if they were rhyming today: De La Soul, KRS-ONE, Rakim, you know the names as well as I do. Public Enemy seemed like a dodgy proposition to the suits when they first came out, but the attitude was, what the hell, who knows with this crazy rap stuff, let’s throw it out there and see if anybody pays attention. By the late ’90s, that uncertainty was gone. This is not to say that there are no longer great hip-hop albums made, because great albums are released every year. I merely point out that there is far less interest in the sort of protean personalities that exist during the classic phase of any style. This is basic corporate theory: when the institution is in a nascent stage, big personalities tend to dominate. Once an institution is mature, big personalities are no longer necessary; eventually, they’re no longer welcome. The game runs by itself. There’s no demand for wild cards in the deck.

The coterie of artists whose personalities defined the classic pop-rock period are now saying goodbye. They’re making closing statements, pulling it together one final time to get their aesthetic estates in order. Since they effectively wrote the rules of album-making, they’ve got certain advantages that younger artists can’t pretend to. Do these make up for the stigma of age — the feeling among some listeners that veteran rockers said their piece and had their turn, and it’s time to turn the floor over to the next generation? Well, sometimes they do, and sometimes they don’t. I’m enough of a softie that I don’t want to throw grandma out in the snow when she might have some wisdom left to impart, just as I’m still enough of a tyro to decry gerontocracy wherever I see it. But I do think that the poptimist argument that it’s unfair to judge younger artists working in alternative styles by the standards of the early ’70s classics is undermined by the influences and models that those younger artists consistently cite. Zeppelin, Nina Simone, Neil Young, Nilsson, Pet Sounds, Motown and Stax-Volt, Dusty Springfield and P-Funk: the names dropped in the press releases I see these days are, pretty much, the same names I saw ten years ago. The album wasn’t supposed to have made it past Napster; here we are in the second decade since the millennium turned, and everybody doing pop, rock, and hip-hop still dreams of dropping a classic full-length.

My favorite single of 2017 was made by a woman born thirty years ago in the frozen fjords of Haugesund, Norway. As far as I can tell, she’s never lived in the United States; I don’t know if she’s ever even toured here. Yet this Scandinavian avant-garde art rocker has chosen, on her lead single, to emulate Dolly Parton circa 1971. Other songs on Music For People In Trouble chase Judy Collins, Grace Slick, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell circa For The Roses. She’s happy to own up to these sources, which were as far in the rear-view mirror for her when she was born as Doris Day and Perry Como were for me. She might be the rare artist who is able to stand up to her sources (Laura Marling is another), but her aspirations aren’t unusual. That’s because those artists and those albums are the benchmark, and they will always be.

Music is both the very best thing that people do and the thing that allows people to be at their best. We are never more ourselves than we are when we are singing, or dancing, or making up songs, or deejaying, or just listening. Music amplifies and broadcasts the strange, irreducible parts of our personalities, those elements that can’t be counterfeited; when you’re in the presence of a real musical artist, you immediately know it’s her, and you know there’s nobody else who can do what she does. Around fifty years ago, rock, pop, and soul artists figured out how to get the album — the forty-minute sequence of songs and musical ideas — to be the ultimate conveyor of personality. Ever since then, we’ve been scrambling to replicate the work they did. We’ve gotten pretty good at it, too: we’re skilled at sound-matching, and song-sequencing, and singing and playing our instruments in a manner that makes our individualities manifest. It’s no shame to admit that it’s never going to be quite as exciting as it was in the classic period; it never is. The qualitative distance is real, but it’s also been exaggerated. The very worst record that’ll be released tomorrow will still be more interesting to engage with than almost anything else you might have devoted your attention to in a year as deadening as 2017. It shouldn’t depress us that we’ll never quite live up to our models. We should celebrate that our models are as world-bending as they are. Thank goodness for them. Go right on copying them.

Single of the Year

- 1. Susanne Sundfor — “Undercover”

- 2. Paramore — “Fake Happy”

- 3. Phoebe Bridgers — “Motion Sickness”

- 4. Tyler, The Creator — “See You Again”

- 5. Vince Staples — “Big Fish”

- 6. Nelly Furtado — “Pipe Dreams”

- 7. Harry Styles — “Sign Of The Times”

- 8. Future — “Mask Off”

- 9. 2 Chainz — “Trap Check”

- 10. Cloud Nothings — “Internal World”

- 11. Drake — “Passionfruit”

- 12. Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee — “Despacito”

- 13. Charly Bliss — “Glitter”

- 14. Morrissey — “Jacky’s Only Happy When She’s Up On The Stage”

- 15. LCD Soundsystem — “Tonite”

- 16. Liam Gallagher — “For What It’s Worth”

- 17. Kendrick Lamar — “Humble”

- 18. Alvvays — “Plimsoll Punks”

- 19. Idles — “Well Done”

- 20. Poppy — “Moshi Moshi”

Best Album Title

Music For People In Trouble. Because we are, you know.

Best Album Cover

See above.

Best Liner Notes And Packaging

The Saint Etienne album came with a little map of the Home Counties, a made-up (and hilarious) police blotter, and an essay that namechecked Orwell and Virginia Woolf. So yes, Sarah Cracknell was speaking my language, and not for the first time. I’d also like to acknowledge Poppy and her evil overseers for a thank-you section that lists most major financial institutions in bold pink type, and instructions for folding the CD insert into a cult hat complete with Illuminati eyeballs. She’s all in on the character, bless her.

Most Welcome Surprise

I was pleasantly surprised that Harry Styles and Nelly Furtado want to be alternarock stars; there’s not a lot of dough in it these days, but at least you get the opportunity to work with real racket-makers. Also, while I’ve always liked Lucy Rose, I didn’t think she had the capacity to make an album as good as Something’s Changing. My real answer in this category, though, is Colin Meloy, who, via the Offa Rex album, proved to me he could do a genuine Martin Carthy imitation. Whatever you want to say about that guy, concede this much: he’s a talent.

Biggest Disappointment

I covered this in the Abstract, but I’ll say it again: it’s been years since an album has disappointed me as much as Melodrama did. Lorde let Jack Antonoff, he of the one chord progression (and an unimaginative one at that) run roughshod over her writing, which is not an outcome I thought was possible in 2013. But I also confess a certain disappointment that Taylor Swift is drinking as much as she seems to suggest that she is on Reputation, if you accept the dubious proposition that her narrators are proxies for her. This year, I sorta do.

Album That Opened Most Strongly

Natalia Lafourcade’s Musas.

Album That Closed Most Strongly

Semper Femina

Song Of The Year

“Nothing, Not Nearly”. Sometimes I think that the entire British folk-rock tradition — from Sandy Denny in Fairport and Jacquie McShee in the Pentangle through Nick Drake and Renaissance, Kate St. John and Beth Orton singing about that abandoned shopping trolley — was all just a buildup to 3:03 – 3:12 on this track.

Okay, page two soon. Thanks for reading along.