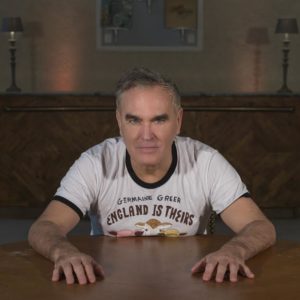

On “I Wish You Lonely”, a musical curse hurled by Morrissey on his hand-grenade of a new album, the fussy old vegetarian compares himself to a humpback whale. Not any whale, mind you; he envisions himself as the last survivor, defiantly swimming through the seas with harpoon-boats in pursuit. Like so much about Morrissey, it’s simultaneously funny and not so funny. For thirty-five years now, it’s never been clear whether his listeners are supposed to laugh. I suspect he wants the authority to crack jokes, but also the prerogative to look down his nose at you if he thinks you’re approaching his lyrics with a surfeit of levity and an inappropriate amount of gravity.

If you know Morrissey at all, and you certainly do, it’ll be clear to you why he identifies with the whale. Humpbacks are intelligent (something he’s positive he is), free-roaming and grand, ugly-beautiful, hounded by bullies. Also, famously, humpbacks sing. Not everybody understands their song, and many, tone-deaf that they are, would deny that that whale is singing at all. Nevertheless, it goes right on with the show.

Like many people who feel marginalized, Morrissey has always been acutely sensitive — both on and off record — to threats to his autonomy and his liberty to speak his mind. Years after topping the UK charts, he still feels very much like an outsider, and he has never been willing to modify or even soften his positions for the sake of the pop game. If you ask Morrissey an opinion question, he’s not going to waffle. You’re going to get an actual answer.

In 2017, few of his fans liked the answers he gave. The nasty nativist streak that has always been present in his writing — from “Panic” through “Bengali In Platforms” and “National Front Disco” and the rest of it — grew too wide for his apologists to ignore. Morrissey made statements that were unambiguously xenophobic and blatantly Islamophobic, too, and went on the record in support of a politician who was odious even by the low standards of the UKIP. In so doing, he appeared to be aligning himself with the ringleaders of the tormentors — the closed-minded thugs who most members of his following feel persecuted by. This all came to a climax in an interview with Der Spiegel which played like an audition for a Prison Planet talk radio gig. Lamely, he claimed he’d been misquoted (nope, you’re on tape, pal). It was all too much, and certain nervous parishioners in the Church of Morrissey ran for the exits. Martin Rossiter, for instance, who did practically nothing but pilfer from the Smiths on those early Gene records, took to the Quietus with a broadside headlined “Why Morrissey Is Dead To Me”. It was like a former Christian washing his hands Jesus; Jesus if he’d gone alt-right.

Me, I’ve got a very high threshold for perturbation. Even back when I was a teenager, searching for all the friends on the pop charts I could find and singing along to “Cemetry Gates” in the back of a speeding car, I always considered the Smiths problematic. I liked discos and the people inside; I always figured I’d be one of the people burned along with the deejay if Morrissey ever had his way with the kerosene. I never wanted that double-decker bus to ram into me. I suspected, very much, that he didn’t either: if he was dead, how would he run his mouth? But Morrissey was a fully-formed character, and thus indispensable in a pop landscape where personality was in short supply. He also wore his flaws in plain sight, which, I had come to recognize, was a hallmark of a legitimate artist. He never tried to hide anything from his listener – it was all right out there, on the surface, gruesome in broad daylight. So even though I never got into World Peace Is None Of Your Business, I figured I needed to give my cranky old uncle Morrissey a spin. There were songs on the new one with such titles as “The Girl From Tel Aviv Who Wouldn’t Kneel” and “When You Open Your Legs”. My rubbernecker’s impulse had been fully engaged.

Low In High School isn’t as good as Vauxhall or Your Arsenal, but it’s probably a stronger and more rewarding set than late-career high points like Years Of Refusal and You Are The Quarry. Neither of those two very good albums made all that much of a splash, so it’s hard to blame this professional attention-getter for turning up the volume and amping up the rhetoric. If that’s all there was to High School, it would still be worth cursory engagement from people whose lives were saved by the Smiths (or so they used to like to say), regardless of the principal’s position on Brexit. But the latest Morrissey is more than that. Yes, it’s abrasive, bombastic, self-righteous/self-pitying, conspiracy-minded – everything the public Morrissey has become over the past decade. But it’s also very funny (as always), peculiarly romantic, lovelorn, properly astringent; acid squirted in the eye of some targets that really do need a good spritz. Seventy per cent sympathetic, thirty per cent abominable – same as it ever was, according to my count.

While nothing on Low In High School contradicts Morrissey’s new identity as a volunteer UKIP spokesperson, it doesn’t lead with the distaste for multiculturalism that has marred so many of his recent interviews. This is, instead, an album about violent conflict: not merely battles between armies, but a war that the singer is convinced, and not without reason, is being waged on people like Morrissey. This is why he opens with a berserk love letter to his fans – he assumes you, long time listener, are something of a humpback whale, too, solitary and hounded by men (always men) who are determined to put the harpoon through softer human specimens. Low In High School argues that war is a choice made not by governments, but by individual male humans who cannot govern their own destructive impulses. I, too, have looked around the country, and the globe, and you know what?, I believe him.

“I Bury The Living”, the stupendous centerpiece of this enraged, justifiably defensive disc, lays the blame at the foot of the Man With Gun: the anonymous grunt, “just doing his duty”, or so we’ve been assured. “Give me an order/I’ll blow up your daughter”, he says, succinct and hard-eyed, hungry to kill. He doesn’t care what the war is about – he just wants an excuse to discharge his weapon. The song is the best rejoinder to mindless Support Our Troops rhetoric since Belle & Sebastian’s “If You Find Yourself Caught In Love”, and it works for the same reason – it isn’t afraid to be offensive. Because war is offensive, people, a million times more offensive than anything a pop star might sing. One song later, on “In Your Lap”, against the backdrop of the Arab Spring, Morrissey ducks and covers as combatants, righteous and fascist, get their jollies by burning, clubbing, and spraying each other. You aren’t responsible for what armies do, he tells us on “Israel”, they are not you. These are the songs that the Decemberists, great as they are, have been trying to write for twenty years; Colin Meloy’s politeness, balance, and sense of decency prevents him from going all the way with the arguments. Morrissey, a goddamned problem, isn’t so burdened.

His remedy: all the young people, he tells us, must fall in love. A little hippy-ish, sure, especially from the guy who wrote “Shakespeare’s Sister”, but I don’t think I’ve heard anything better, or more practical, from the so-called authorities lately. Also – and he is dead serious about this – he requests that you stop watching the news. I think he’s right about that, too. Broadcast journalism got caught in the rapids around 2013 and has since gone right over the waterfall, and it’s mostly been yelling and kicking up a dangerous froth ever since. They’ve mastered psychological techniques to keep you tuning in, waiting for the big revelation that never comes. I appreciate Morrissey pointing the finger, and putting it to us as straight as he does, just as I commend him for what appears to be a legitimate concern for the mental state of those he counts as members of his tribe. On Low In High School, he really does sing like he’s worried about you, Morrissey listener, ostensibly fey individual who, for all he knows, may actually be a girl, clinging to passive resistance in the face of toxic masculinity. All of his songs have always been pitched at you, of course – that’s why you scribbled the lyrics on your notebook. But he’s never made the stakes quite as clear as he does here.

No matter what they tell you during election years, artists aren’t terribly interested in politics. For the most part, an artist’s prime responsibility is to the art, which, in a capitalist society, means securing enough funding to do the next project. That’s it; that’s the driver, and there’s no shame in it. A real artist will make all kinds of horrid compromises and enter into relationships of complicity with any number of ghouls to make sure the next album comes out. I think we fans of popular music have come to accept this, just as we acknowledge that most “statement” records don’t really make statements at all: they say exactly what you’d expect them to say given conventional wisdom and the general liberalism of the pop audience. Morrissey, though, is different. He wants fame and fortune as badly as the rest of the pop stars do, but some ancient injury that won’t heal (I think I know what it is) makes him incapable of going along with bland consensus or playing to the crowd. I heard hundreds of political records in 2017 – records from old artists immobilized by guilt for what their generation had done and young artists determined to be broadly inspirational and inclusive. The only singer who convinced me that he’d actually stand up and fight for me – the only one willing to jeopardize his career in order to speak out on behalf of his audience as he imagines it – was Morrissey, for better and for worse. It’s there in the high note he reaches on “Home Is A Question Mark”, and in the way his voice breaks at the climax of “Israel”, and in the gritted-teeth delivery of “I Bury The Living”, and in the very sharp words he aims right at your beleaguered eardrums. If it’s all an act, it’s a heck of a good one.

You know what?, it’s not an act.

Best Singing

Steven Patrick Morrissey

Best Rapping

Kokamoe is an old guy who jumps on buses in D.C. and starts rapping. He’s been doing it for decades, which means he’s been in town for quite a bit longer than Devin Nunes (R, CA-22). The “Kokamoe Freestyle” is the virtuosic peak of GoldLink’s At What Cost, the year’s best pure rap album, and a needle-drop directly into the groove of the nation’s maligned capital. It’s not so much a tribute to Kokamoe as it is a celebration of the local color of a city that, too often, is hated on by the rest of the country. The real D.C. is right there, somewhere past the monuments and the National Mall. GoldLink wants to show you.

Best Vocal Harmonies

Tie between Harry Styles’ multi-tracked Southern Cali-voices on “Ever Since New York” and Lana Del Rey “singin’ with Sean” Lennon in awe and wonderment at the great spinning wheel of schlock that is showbiz. My favorite backing vocals were done by the Big Moon, the outfit that supported Marika Hackman on I’m Not Your Man. Their album has its moments, too.

Best Bass Playing

Much as I’d love to vote for the Dutch Uncles’ art-funky Robin Richards here, I’ve got to go with James Murphy for his successful Tina Weymouth impersonation. Thousands upon thousands have tried. Only a handful have survived to tell the tale.

Best Drumming

Evan Burrows of Wand is my man this year — his playing demonstrated a neat familiarity with punk and jazz and jam-band free-for-alls, not to mention proggy drama, and he jumped between the styles with more grace than genre-hoppers ever seem to manage. While I’m at it, I want to send a great big shout to the rhythm section on Lucy Rose’s Something’s Changing: they really did capture that Sirius XM The Bridge “mellow classic rock” sound that I thought had gone out of style with Phoebe Snow.

Best Drum Programming

Pop singers over trap beats: that’s become a horrendous cliche, and one we all wish would go away in 2018. But Lana Del Rey isn’t just any pop singer — she’s the Queen Midas of absurdity, and everything she touches is blown up to a ridiculously epic scale. She’s also so closely in tune with Rick Nowels that he can anticipate her emotional states and reflect it in their beatmaking. Those heart-flutters and tight-throat sobs, the sudden accelerations of thought and roller-coaster drops into melodrama are all present on Lust For Life. They’ve got this character down pat. The miniseries ought to be lots of fun.

Best Synth Playing/Programming

Bobby Sparks on Nelly Furtado’s The Ride.

Best Piano Or Organ Playing

If you like piano-playing singer-songwriters, 2017 was your year. Susanne Sundfor, Roger Waters, Tori Amos, Randy Newman, Lucy Rose, Steven Wilson — they all took to the eighty-eight with sensitivity and skill. Elizabeth Ziman of the Catapult was the flashiest (check out “Mea Culpa”) and that counts for plenty to this showoff over here. But the very best was Emily Haines.

Best Guitar Playing

Los Macorinos.

Best Instrumental Solo

Bobby Sparks’s organ ride at the end of “Pipe Dreams”. It’s the rare pop star willing to share space on her single with the organist. Think of that gesture of magnanimity the next time you’re tempted to make fun of Nelly Furtado’s name. Oh, wait, that’s not you who does that; that’s me. Sorry, Nelly.

Best Instrumentalist

It was a hell of a year for Greg Leisz. Not only did he add his slide guitar to records by the usual classic rock characters, he also made a significant incursion into alternative music. St. Vincent, Father John Misty, Susanne Sundfor, Haim, Phoebe Bridgers — Leisz decorated all of those albums. He plays on two of my three favorite singles of 2017. Despite all of that, he’s still a bit unsung. Call him what he is: one of the best and most versatile guitar players working today in any style.

Best Production

No I.D. for 4:44. He had Jay-Z’s consent to try to make a classic album, commercial aspirations be damned; he had to keep up with his wife, and couldn’t be bringing home any sub-standard bags of groceries. But Jay is such a brand that No I.D. was left with a difficult needle to thread: the music had to be cohesive, and allude to Hova past while never overwhelming the listener with nostalgia. Come to think of it, that’s the same challenge Nigel Goodrich overcame on Is This The Life We Really Want? Those two should get together, swap notes, trade stories about their crazy bosses.

Best Arrangements

I sat through years of look-at-me misogyny and press-baiting homophobia and kill people burn shit fuck school — a whole lot of nonsense, in other words — to get to the moment on “See You Again” when Tyler lets the brass pour all over the track like warm honey on a biscuit. Truth is, he was never convincing as a anti-social tough guy. I saw him as a would-be soft-rocker and maker of beautiful music, in the Englebert Humperdinck sense, from the outset. If you haven’t watched his tiny desk concert, it’s by far the best one I’ve seen. What a goof, what a clown, what a total, wonderful nerd. I still can’t believe the Moral Majority was ever scared of this guy.

Best Songwriting

Bill James, infamously, once called Don Mattingly “100% ballplayer, 0% bullshit”. That was it; that was his whole comment on Mattingly’s career. I watched Mattingly play, and I know what James meant — he never wasted one moment of his too-short run under the limelight indulging in extraneous nonsense. He had a talent, and he stayed true to it as long as he could. Anyway, I’d like to say that Natalia Lafourcade is 100% musician, 0% bullshit, but I can’t leave it at that: I’m too much of a blowhard. Sometimes marketed north of the border as Mexico’s answer to Norah Jones, she’s really more of an indiepop version of Lila Downs. Like Downs, she’s got an encyclopedic understanding of Latin American folk forms and the energy of an international pop star; unlike Downs, who’s a bit of a roughneck, Lafourcade possesses a voice from twee heaven and a light touch on the faders. When she puts the flowers in her hair and plays her ukulele, it’s like somebody opened the otter enclosure: it’s cuteness overload that the human eyeballs are not equipped to handle. I’m still scarred, and the scars are pink and taste like sugar dots. Hasta La Raiz, which was either the best or second-best album of 2015, played like a cross between Belle & Sebastian and Julieta Venegas that I thought existed only in my lucid dreams; Musas, the new set, is pure, patriotic engagement with the Mexican folk tradition from a Veracruzana linda with a not-so-subtle message for bigoted Americanos. Some of the songs are penned by trad., and some are Lafourcade originals, and I’ll bet you a plate of split-pea tlayocos that you’ll never be able to tell which are which. Here’s a hint: hers are the ones that sound even more like Latin jazz-folk standards than the actual jazz-folk standards. She is amazing; we’re not worthy; etcetera; etcetera; my favorite artist in the world at the peak of her powers. New album next week!, I am hyperventilating.

Best Lyrics On An Individual Song

Jay-Z’s “Marcy Me”. Dense, old-school rhyme about dense, old-school New York City.

P.F. Rizzuto Award For Lyrical Excellence Over The Course Of An Album

The songs on Dark Matter concern, in order: a hypothetical debate between smug fundamentalists and clueless scientists, the Bay of Pigs invasion reimagined as an effort to kidnap Celia Cruz, the psychology of Vladimir Putin, a woman berating her children from her deathbed, the theft of the identity of the bluesman Sonny Boy Williamson, the masturbatory thrills of the conspiratorial mindset, a funny-looking man’s disbelief in the face of his beautiful wife, a beach bum about to be drowned by rising sea levels, and a crushed old man who has lost his youngest son — probably to heroin addiction, but you can’t expect Randy to give you all the specifics, now, can you? He sets the pace. The rest of us jokers chase.

Band Of The Year

Elbow. Ssh, they don’t like calling attention to themselves.

Best Live Show Of 2017

St. Lenox at the Sidewalk Cafe.

Best Music Video

All the fabulous clips for Musas songs aside, I was knocked dead by this video for “Magpie Eyes”. New Jersey has its own Home Counties, and Union, where I grew up, is one of them. I don’t recognize the architecture, not exactly, but I understand the sentiment: there’s a big city out there, and by many signs it isn’t that far away, but it may as well be on the other side of the moon for all it intersects with your life. Everything around you feels simultaneously functional and dated — you know it’s not going to be replaced, but you’re vaguely conscious of a standard by which it would all appear worn out and maybe even risible. You can spend your teenage days dreaming, or you can appreciate the strange, eerie, subtly cosmopolitan beauty of what you’ve got. The tower blocks, the rail stations, the right angles in concrete, the longing faces of your friends.

Sun’s setting, that’s all for today. I should probably proofread this, no? Next essay will be the pseudo-political one. Sorry about that; the good news is that there are plenty of categories to come. Also, there’ll be a last word, and this one is long overdue.