To some, I guess, they were a stoner band – they made songs ideal to light up to. That’s a fine approach to Pink Floyd, even if it wasn’t mine. For other fanatics, Pink Floyd were soundscapers in the prog tradition, immediately identifiable instrumentalists who made music that was effortlessly immersive. Put on a Floyd album and get lost for forty-five minutes; I certainly did plenty of that. Still others saw them as a band of might-have-beens: what if Syd hadn’t lost his mind, what if Rick and Dave had kept on singing, what if Roger hadn’t, to paraphrase James Mercer, grabbed the yoke and flown the whole mess into the sea?

Yet to me, Pink Floyd has always been a concept band. It was because of their mastery of concept – their ability to buttress a philosophical or political idea with flourishes and sonic coloring that reinforced its meaning – that Pink Floyd became, along with Yes, one of the pillars of the temple of rock where I knelt at night. Yes was the sound of heaven: the world that I wanted, an eco-utopia of perpetual change and elfin magic and the revealing science of God. Pink Floyd was the world as it was: the smokestacks and the ticking clocks, the pigs and dogs and sheep, and always some mad bugger throwing up a wall.

Roger Waters, for all his faults (and to his credit, he’s always worn them in plain view) was the concept-keeper for the Floyd. Without him, they would merely have been a great band; with him, they stayed on topic and theme better than any rock group ever did, or ever will, probably. It was Roger who told Syd’s story in diamond-hard imagery on Wish You Were Here, and laid out the breakdown of the postwar dream in The Final Cut, and on Animals, ushered you into the coldest shower you’ll ever take – a vision of society that, because of its ruthless accuracy, still rings like an alarm all these years later. Roger kept it going in his solo career, too; even if he didn’t have his former mates to back him up with music worthy of his ideas, he kept those big ideas coming.

While Pink Floyd kept those sets tidy, it was, by 1977, apparent that Roger was working on a grand concept that transcended single albums. He had something to say about war and the welfare state, greed and surveillance and state-sponsored distraction and the price of liberty, and our human obligation to take care of each other. Sometimes it took the shape of a personal story: a father he never knew, “buried like a mole in a foxhole” at Anzio, as Roger, who was desperate to make that sacrifice mean something, sang in “Free Four”. Sometimes it drew from classic dystopian literature, like the echoes of Orwell and Bradbury in Animals, and sometimes its inspiration came directly from headlines about miners’ strikes and trouble in the West Bank and Gaza. This was sanctimonious at times, and it sure could be strident, but it was never forced. It was all an expression of Roger’s soul, and in singing it with the passion that he did, he was playing according to the rules of his chosen style. He expanded the parameters of what rock could be. He was making progressive music, even though he thought he was.

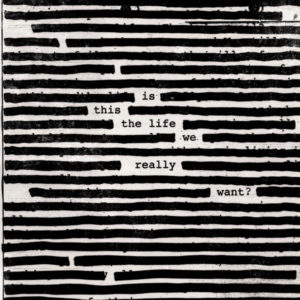

His monomaniacal pursuit of his vision wrecked Pink Floyd. The other players in the band were way too good to be marginalized. In retrospect, it’s easy to blame Roger for the estrangement that followed The Wall; nobody likes a guy who puts his sociopolitical agenda ahead of his relationship with his mates. Yet Roger Waters was driven, as many great artists are, by a story he absolutely had to tell – and fifty(!) years after The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, that ambition is still paying artistic dividends. Is This The Life We Really Want? is the culmination of a through-line in Roger Waters’s writing that begins with Corporal Clegg’s wooden leg and threads through Obscured By Clouds and the stealth-socialism of The Dark Side Of The Moon, the despair of “Another Brick In The Wall, Part 1″ and the elegy for liberal democracy on “The Gunner’s Dream”, the quiet outrage of the When The Wind Blows soundtrack, and the unanswerable moral rage of “The Bravery Of Being Out Of Range” from Amused To Death. All of that is present and profoundly reinforced on the new album, which is the most succinct elaboration of Roger Waters’s worldview ever waxed, and the only rebuttal to the State Of The Union address you’ll ever need. With Is This The Life, Roger has done something that few artists, even great ones, ever manage to do. He’s stuck the landing.

It may remind you of Pink Floyd. That’s intentional. Roger has always loved callbacks, and as it’s his catalog, he’s free to re-use it however he likes. Nigel Godrich, who produced this set, is an obvious Floyd obsessor who knows the discography backward and forward, and he’s pulled off an impressive balancing act – he alludes to Roger’s past without overwhelming the listener, or the singer, with it. The record that Is This The Life We Really Want? most closely resembles, in tone and theme, is The Final Cut, and if you’re one of those Floyd fans who can’t countenance that one because of the way Roger was treating his (soon-to-be-ex) bandmates, you might want to run these two back to back to remind yourself just what was at stake.

The Final Cut is a record about a missed opportunity: our chance, according to Roger, to refashion society according to egalitarian principles in the wake of World War II has slipped through our fingers, and now we’re living with the consequences. Just like his role model Jeremiah, he names names, howling his head off about Margaret Thatcher and Leonid Brezhnev and Galtieri, and you, First Worlder, who has put material comfort ahead of your responsibility to your neighbors. The threat of nuclear holocaust hangs over the whole set, but the proximate cause for all the shouting was the Falklands War, which Roger saw as grubby and intemperate backslide into pointless militarism. Confrontational as it is, the album contains some of the most beautiful poetry ever written by a rock band, including the second verse of “The Gunner’s Dream”, a distillation of the promise of social democracy that beats the stuffing out of any political speech I’ve ever heard. If pop music is, at its best, an attempt to fill up the infinite space between the people we are and the people we wish we could be, here was a reach farther than most artists dream, let alone attempt.

The band, however, was coming apart, and I can’t deny The Final Cut sounds fractious. Roger, who has always sung like a wailing revenant, is even more cracked and exhausted here than he usually is. Unfortunately for all of us – Roger included – the world has given him another chance to make many of the same points. Thirty-four years after The Final Cut, we’re right back to petty nuclear brinksmanship, authoritarianism, and near-psychotic disregard for the welfare of our fellow travelers on the planet. On Is This The Life We Really Want?, Roger illustrates our predicament with graphic images that would’ve seemed over-the-top if circumstances hadn’t proven them dead right: I like the description of life in 2017 as a seat on a windowless, doorless private plane manned by an insane crew, but you may be more moved by the dead child face down on the beach, or the woman killed by drone strike as she cooks rice for her family, or the tank crushing a student, or a home, or a pearl. This is ugly stuff he’s entertaining us with, no doubt, and it isn’t for the faint. Same as it ever was, Pink Floyd fan. Somebody has to preach, right?, and since the churches have abdicated their positions as moral arbiters, it’s down to the pop stars to bring the fire and brimstone.

While other members of his cohort – Randy Newman, Paul Simon, Ray Davies, etc. – have succumbed to various flavors of despair, Roger Waters continues to insist that we’ve got options. What differentiates us from the bug on the wall is our capacity to act selflessly and open our hearts to the stranger and the refugee. When we stand by, silent and indifferent, and allow the suffering of others to continue, we’re choosing to dehumanize ourselves – which, according to Roger, is exactly what we’ve been accomplishing. Note that the album title is a question: we’ve all got the option to choose humanity over anthood, so why don’t we? Roger’s tone throughout is one of anguished disbelief – this can’t be the life we want, can it? These choices we make, they serve no one, do they? Yet we keep making them. This time around – and this hasn’t always been true on his solo records – he’s got a band who’s right there with him, illustrating his poems with performances that feel anguished, weary, accusatory, repentant, all the things that the music suggests. As for Roger himself, he’s still broken-hearted when he mumbles and properly astringent when he shouts. He’s also revealed a heretofore dormant talent for playing the piano. Nothing he does is flashy, mind you, he hits the keys slowly, and dolefully, like he’s knocking on your door to deliver the disastrous news.

Is some of this grumpy-old-man business, a litany of bellyaches about the parlous state of the world? Well, certainly, and if you want to argue that there’s no place for that in pop music, on certain dark days I’m willing to concede the point. But if anybody has earned the right to complain, it’s Roger Waters. Fifteen million copies of The Dark Side Of The Moon were sold in the United States. Songs bearing Roger’s heavy lyrics have been in rotation on classic rock stations for decades. It’s not that he hasn’t been heard, it’s that he hasn’t been heeded. How many of those people who chanted at rallies about building the wall and keeping immigrants out have copies of Pink Floyd albums in their collections? How many of them attended a Pink Floyd concert, or sang along to a song on the radio? Quite a few, I’d imagine. The generation that Roger Waters has been addressing, so eloquently and passionately, for sixty years?, those guys turned out to be real pieces of work. We’re not much better. For more than sixty million Americans (not to mention voters in the UK who’ve got their own problems) Roger’s poetic verses meant nothing. I’m not sure how any artist could try any harder, or believe in his causes any more fully, or make his case any more plainly. Honestly, it’s a minor miracle that Is This The Life We Really Want? is as even-handed as it is; if he’d gone straight off the rails and put out an album of fist-shaking rock, I wouldn’t have blamed him. Instead, he’s given us another perfectly balanced cycle of songs, rueful and gorgeous in all the right places, thoughtful, imploring, open-hearted. I’d like to think that Governor Kasich, self-proclaimed Pink Floyd fan, heard it, and let the lessons sink in. I’d like to think that it mattered to you. It couldn’t have mattered more to me.

Album Of The Year

- 1. Roger Waters — Is This The Life We Really Want?

- 2. Saint Etienne — Home Counties

- 3. Laura Marling — Semper Femina

- 4. LCD Soundsystem — American Dream

- 5. Tyler, The Creator — Scum Fuck Flower Boy

- 6. Randy Newman — Dark Matter

- 7. Elizabeth & The Catapult — Keepsake

- 8. GoldLink — At What Cost

- 9. Paramore — After Laughter

- 10. Susanne Sundfor — Music For People In Trouble

- 11. Morrissey — Low In High School

- 12. Natalia Lafourcade — Musas

- 13. Marika Hackman — I’m Not Your Man

- 14. Lana Del Rey — Lust For Life

- 15. Elbow — Little Fictions

- 16. Lucy Rose — Something’s Changing

- 17. Jay-Z — 4:44

- 18. Wand — Plum

- 19. Emily Haines & The Soft Skeleton — Choir Of The Mind

- 20. Drake — More Life