In my life, I’ve encountered people who are truly committed to social justice, equality, fairness, and a political program that might reasonably be called progressive. I’m always struck by how many of these people are Rush fans. Dedicated fans, too; fans who’d surely count the members of Rush among their favorite musicians, if not their personal heroes.

I can think of a few reasons why this might be. A commitment to social justice is, in my experience, a mark of intelligence, and Rush has always cultivated a smart fanbase. Rush wrote sci-fi at a time when not many rock bands did — songs designed to resonate with the same sort of kids who found Asimov and Bradbury provocative, or Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. There was a Solar Federation, and it was oppressive, and it was the moral responsibility of the thinking individual to stand against it. Rush taught its audience to see systems, and patterns, and encouraged listeners to dream of a better and purer way forward. Three of those dreamers were the members of Rush themselves, who, on and offstage, threw the weight of their celebrity behind the twin causes of mindfulness and compassion.

So it saddened me to see Ayn Rand’s name in many of the obituaries and appreciations of Neil Peart. Objectivism was part of Neil’s intellectual development, as it was for many young men, and because Peart always wrote about what he was reading, Ayn Rand’s ideas showed up in some of his lyrics. So did echoes 0f Samuel Coleridge, and Arthur C. Clarke, and, most famously, Mark Twain. Neil gave the impression that he never discarded an idea he encountered in a book. By the time he wrote the songs that made Rush world-famous, he’d already drawn what he needed from Objectivism and moved beyond it.

Nevertheless, Rand sticks to Rush like a rust stain. I’d like to put the blame on the Boomer generation of rock critics, who hated Ayn Rand almost as much as they hated Rush, and still miss no opportunity to beat Rush with the stick of Objectivism. I can’t, though, because Neil Peart really *did* write several early songs — good songs — that made his appreciation for and understanding of Anthem apparent. If Rand herself had heard those songs, she… well, she probably would have considered Rush degenerate. But she would have liked the lyric sheet. She’d have noticed her fingerprints all over them. Ayn Rand can’t, and shouldn’t, be written out of the Rush story, no matter how much fans of the band would like to recuperate Peart’s rep on behalf of genteel Canadian social democracy. The young Peart had a view of socialism and communism, and it wasn’t a favorable one. What’s important to remember, though, is that even at his most philosophically vulgar, Neil Peart had a pronounced moral sensibility miles beyond anything articulated in any of Ayn Rand’s writing. And Neil Peart wasn’t vulgar for long.

When Peart wrote “2112”, he was 23 years old. He was still pretty new to the band, and the band was pretty new to the airwaves. The record company gave Rush a tacit ultimatum before the album came out: write something that sells, or that’s that. It’s possible that Peart had a grievance against power structures — especially the sort of authority figures who weren’t demonstrating the imagination or courage necessary to appreciate a band like Rush. As a young man possessed with a world-class talent, he must have appreciated Rand’s condemnation of mediocrity. Peart replaced the Anthem lightbulb with a guitar, and positions rock as sedition against a totalitarian state — a theme that would soon become a trope, culminating in the near-parody of Styx’s Kilroy Was Here. In tone and temperament, it’s not all that far removed from Paul Kantner’s Blows Against The Empire, or, for that matter, Fahrenheit 451 or A Canticle For Leibowitz.

“2112” was an unexpected commercial triumph that established Rush as a band with a future. If Peart had been a true denizen of Galt’s Gulch, he would have seen this turn as a personal vindication and become insufferable. Instead, he pivoted, and penned his first set of mature lyrics. A Farewell To Kings is an album about the moral inadequacy of society — its wayward rulers in particular. The Cinderella Man is cast out and rejected not because he’s a misunderstood Übermensch, but because he carries a message of radical love that his peers and leaders aren’t ready for. Neil Peart was certainly no Christian, but there are overtones of caritas in his writing: he asks us to forge a new reality/closer to the heart, which is prog-rock speak for sympathetic identification. A Farewell To Kings couldn’t have been written if Peart hadn’t first grappled with Rand’s ideas on the prior album, and pushed past them. He wasn’t overwriting “2112.” He was complicating it.

Peart’s final flirtation with Objectivism makes this clearer. The members of Rush developed a tendency to laugh off “The Trees” or dismiss it as a fairy tale, and it’s easy to see why: the song’s political implications are obvious, and they’re delivered with the sort of bluntness that upsets the ideologically squeamish. Yet I believe that “The Trees” is an essential song in Rush’s catalog, and I don’t think it’s possible to apprehend the scope of Peart’s lyricism without grappling with it. The song, if you don’t know it, is about a revolt in a forest in which the shorter maples punish the taller oaks for hogging the sunlight. In the end, in a wonderfully brutal image, the trees are “all kept equal/by hatchet, axe, and saw.” The maples have not merely seized control and enforced equality in the most menacing way — they’ve also convinced themselves of the nobility of their violent act. It should be clear that Peart is writing about communism, and doing so in a way that draws on his absorption of Ayn Rand’s political philosophy.

But wait a minute: Peart doesn’t let the oaks off the hook, either. Their undoing is, at least partially, their own fault. Rush tells us that the bigger trees are self-satisfied, and describes their active refusal to understand the complaints of the maples. In “The Trees,” the oaks are worse than arrogant, at least from the perspective of a loud rock band: they’re deaf. It’s their inability to sympathize with their less fortunate neighbors that puts the forest in peril. And this, from Hemispheres on to the very end of the band, becomes a driving theme of all of Rush’s work. Human society, cruel as it is, can be salvaged if we listen to each other respectfully and allow our hearts to open. It’s an optimistic and deeply Canadian vision, and Rush, in spite of the occasional darkness in their music, was an optimistic (and deeply Canadian) band. Peart believed that gains was possible and disaster could be averted, and that people really could forge that new reality closer to the heart. And this is, I think, why so many self-identified progressives adopted Rush as a patron band: they were the rare rock conceptualists who actually believed in progress. Compare to Tony Banks’s near certainty that human beings were doomed to continue to make the same mistakes over and over, or Peter Gabriel’s dredging and plumbing of the destructive unconscious, or Roger Waters’s scalding fatalism about the failure of the postwar dream, or the Airplane’s last-ditch anti-authoritarianism, or Jon Anderson’s prophesies of ecological collapse and fears about life lived too close to the edge.

And while Neil Peart couldn’t, or wouldn’t, have written “The Trees” without a push from Anthem, the song reminds me just as much of a better story that libertarians also love: “Harrison Bergeron.” Vonnegut’s dystopian fantasy from 1961 is often read as a reaction to the excesses of Soviet-style socialism, but really, it confronts a human impulse native to no particular god or government. Harrison is a rebel against a society that has no tolerance for demonstrations of excellence that might make the talent-free feel bad about themselves. Those with innate ability accept their government-provided handicaps happily, in the name of the social order; for instance, one character with remarkable intelligence wears a special headset that buzzes, rings, and distracts him every time he formulates a coherent thought. The story makes clear that the character’s decision to wear the headset is, at least in part, voluntary: he’s internalized the egalitarian principle so thoroughly that he’s willing to punish himself for his own marks of distinction.

The first time I read this story, I thought Vonnegut was being hyperbolic. But the older I get, the more I realize that the world of “Harrison Bergeron” isn’t much different from the one we inhabit. We have indeed designed a device that broadcasts signals and static worldwide, and which rings, beeps, flashes, and generally discourages us from sustaining and developing thoughts beyond their most rudimentary form. You’re on it right now. If you’ve managed to read this far without clicking on a distraction or checking a feed for a jolt of novelty, well, you’re probably a Rush fan. Neil Peart dreamed of an Analog Kid whose natural purity granted him immunity from the normalizing tendencies of the techno-state: today’s Tom Sawyer, whose mean, mean stride contained reserves of integrity and self-possession. Straight through Clockwork Angels, Peart believed that resistance was possible, and that renegades were real, and that there existed a red Barchetta fast enough to outrun the heavy-handed enforcers of the Motor Law. Maybe that red Barchetta was you.

I’m not much of a progressive, and Rush was never my band. Yet their music is, for me, as it is for so many others, indelible: missives from a writer who was always too decent to mislead his audience. On MTV, many of my other favorites pushed me a fantasy of an adult world defined by adventure and transgressive behavior. Neil Peart couldn’t do that. He was the first I heard who was willing to describe my reality as it was, and as I experienced it – suburban sprawl as an expression of a imaginative deficiency, suspicion of anything out of the ordinary, a widespread longing that society seemed increasingly unable to satisfy. Peart’s nods toward Ayn Rand weren’t even the price we had to pay for a critique of conformity as blunt and beautiful as the one in “Subdivisions,” because by the time he got to Signals, that stuff was all in the rear view mirror. I’m just gratified that something worthwhile came of Objectivism, and it didn’t just resolve to Paul Ryan trying to take basic services away from poor people.

One last thing: while other great rock writers sang about harmony but behaved abominably to the people in their lives, Peart practiced what he preached. He was, by all accounts, a kind and generous person, one who would write thoughtful, caring letters to listeners and who treated everybody in Rush’s orbit with courtesy. His famous aversion to the limelight was real, but he never stopped trying to improve himself as a writer or as a performer. While other great rock bands fell apart because of the egos of the artists, Neil, Geddy, and Alex hung together, tight, until it became physically impossible for the group to continue. Anybody who has ever seen Rush in concert knows that the connection – and the friendship – between the bandmembers was a real and beautiful thing. Rush was a demonstration that Neil’s ideas about respect and openness and the courage to deviate from the norm weren’t bullshit – that people living by these principles really could function, and flourish, and achieve the greatness that they aspired to.

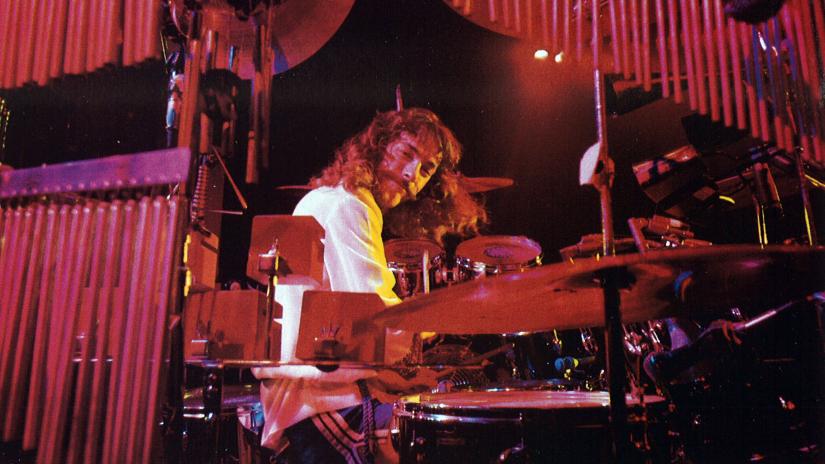

Oh, and Neil Peart could play the drums a little, too.

Best Singing

The Sunday Service Choir.

Best Rapping

Saba, who continues to make a strong case for himself in the Best Rapper Alive sweepstakes. This time around, he does it in the context of a posse project, and even if his Pivot Gang pals aren’t good enough to keep up (few would be), they do impart personality and pass him the rock so he can score with decorum. Joseph Chilliams – who, as it turns out, is Saba’s little brother – makes a decent ersatz Phife Dog, complete with references to small-time screen celebrities you forgot about and pro athletes and cartoon characters you didn’t. The other dudes acquit themselves well as color commentators too, even if “pull up with that Smith like Morrissey” is a few decades out of date. It all does make you wonder how Walt would have fit in had he not been, as you heard, killed for a coat. In a way, You Can’t Sit With Us drives home the tragedy of his death even more than Care For Me did.

Best Singing Voice

John Van Deusen. More emotionally charged music from an emotional young man playing his electric guitar and howling in an emotionally effulgent fashion. If there was only a shorthand way to refer to this style! In fairness, I doubt that the Emo Council would accept John Van Deusen into the brotherhood: for all the Gibbard in his sound, the echoes of Frightened Rabbit are louder. The psychic connection between the Pacific Northwest and Scotland run deeper than the fjords, so I have to believe that Van Deusen is acquainted with the same maritime despondency that took out Scott Hutchinson. Regardless, he’s come with the best batch of hooks I’ve heard on an, um, emotionally forthright guitar album in awhile, and he’s an outstanding singer, too, acrobatic without being showy, and nicely tethered to his well-wrought melodies even when he gets worked up. Moreover, I’ve heard he runs a boardgame store in Anacordes, Washington. so we’re probably simpatico. If you’re ever in Anacordes, drop by and pick up a copy of Agricola; I’m sure he stocks it.

Best Guitar Playing, Acoustic Division

Adrianne Lenker

Best Guitar Playing, Electric Division

The hot Sahel wind blows through the frets of Fenders and Gibsons. I’m never going to know what Tinariwen is singing about, so I’m glad those guys speak with their hands in the international language of Stratocaster. That goes for Fatoumata Diawara, too – the press stuff says she’s decrying female circumcision and the shoddy treatment of refugees, and yeah, I’m just going to take her word for it. Mdou Moctar is from Agadez in Niger, which is on the southern fringes of the Sahara and a major jumping-off point into the void for migrants fleeing Africa for cooler pastures. It’s a place, in other words, that’s stitched like a burr into the interwoven globe, and Mdou plays like a guy hip to every vibration on every string. I hear Fela and Hendrix, but also Black Sabbath and Jimmy Page, and especially Richard Thompson. Mdou can’t really sing, so he basically solos straight through the album, and if you’re hungry for guitar pyrotechnics, this is worth a spin. Drawing connections between Nigerian funk and heavy metal, Caledonia soul and soca, and folk music of the Celtic diaspora – Van the Man could tell you all about it, if he was in a chatty mood.

Best Bass Playing

Sego Sucks is a scruffy, sleazy, wordy rock record made by fans of Talking Heads, LCD Soundsystem, and (especially) the first two Beck albums. The frontman, who is occasionally desultory and always a little caustic but never, ever malicious, and often seems on the verge of flying into a tizzy, often puts me in mind of Jesse Hartman of Sammy. He’s got that same drowned rat/drowning ironist charisma. It works in a rock context, or it used to, anyway. You might see his constant slippage from bemusement to bewilderment as a defeatist dodge; he’s a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill him, etc. But I reckon you will appreciate his greatest asset: bassist Alyssa Davey, an absolute monster with a sound as meaty as a porterhouse from peter luger. Just like a good punk reprobate ought to, she bullies the strings with total depravity. Davey ought to be playing with the Stones or the Who or somebody, rather than a dirtball combo from Utah, but for now, they’ve got her, and as long as she’s handling the bottom end, they’re free to put fuck-all over the top and it’ll work: guitar squall and narcoleptic nyah-nyahs and USA chants and whatever else crosses their feedback-addled minds. Not all of these gutter jams merit close engagement – sometimes they’re just dragging you through the dirt to see how much muck you can take – but “Neon Me Out”, the kickoff, is one for the ages, and it’s probably already in a trillion car commercials. The chorus attaints that kaleidoscopic quality I associate with Kula Shaker circa “Govinda”: you really do think you’re catching a glimpse of God, or perhaps Jerry Garcia.

Best Drumming

I didn’t expect Wand to turn into Radiohead quite so soon. Guess I should have known from the general bendsiness of “Bee Karma” (note second word) from Plum, but silly me, I thought Cory Hanson was just dipping a toe into the pool. Laughing Matter goes on for ninety years or so, and parts of it are taxing, but to their credit, they never try to get over on texture alone. Or effrontery, for that matter, although they must exist in a constant state of temptation by the lure of their own machinery. Even when the music gets noisy or imitative of OK Computer, the next interesting harmonic or rhythmic idea is usually only a guitar squall away. After a year of too-brief projects, it’s downright nice of Wand to give us a sonic ocean to explore. I like the Galaxie 500-ish one that Sofia Arreguin sings about her plane ride, and the one in which Hanson takes too much Advil and urinates on himself, and especially “Wonder”, which could be the centerpiece of any old Uriah Heep or Blue Oyster Cult album and will remind you why wand is the psychedelic band of the moment, no matter how much they dig Thom Yorke (a lot, apparently.) Also, and this is critical: Evan Burrows, their stupid-good drummer hasn’t gone anywhere. He isn’t any less stupid-good than he was on Plum.

Best Synth Playing

I take it as a given that Americans do not and cannot understand Joe Mount’s sense of irony. But I’ve recently begun to suspect that Brits don’t get the joke either. For instance, there’s the slow and drumless one on the new Metronomy album on which Joe keeps singing, over and over, in his most mealy-mouthed voice, about how he was thrown out of his rock band for playing the drums too fast. Then, almost as an afterthought, he slips in a verse about a rejected proposal. This is a preoccupation on Metronomy Forever: there are wedding bells but they’re not for you, and when Joe raises his head to hit on the woman who is like salted caramel ice cream, you just know he’s going to screw it all up. The key, I think, is the very last song, which only seems slight if you aren’t paying attention to the words. Joe slips a mixtape to a girl at a dance, and she doesn’t call him back; he figures, well, that’s that. Ten years later, her brother tells him that he loved the tape, and the two blokes end up getting a drink together at a bar. This is music as compensation for something lost, a lubricant for missed connections and crossed wires, and it’s presented here without acrimony by a guy who has always been a better storyteller than the EDM crowd appreciates. As for the quality of the synth textures, well, you already know.

Best Piano Playing

Phil Cornish from Sunday Service. The first time I walked into New Hope Church in Newark, I didn’t understand why there were boxes of tissues on the ledges by the walls. Fifteen minutes into the service, I got it. There have been other great gospel albums released in the past few decades, but none approaches the transformational force of a real service like this one does. And no matter how much Kanye frustrates me, I’ve got to give him credit for making this happen — and reminding us again that everything we love about pop presentation comes directly from the African American church.

Best Vocal Harmonies

Harry Styles on Fine Line. Harry’s a classic rock fan, so I have to think that the sonic references to Yes, and The Zombies, and The Association, and The Mamas And The Papas are 100% intentional.

Best Drum And Instrument Programming

Igor. So Tyler is a full-blown queer now! Welcome to the club, Tyler. I think it’s a good look for him, and it’s salutary for the rest of us. It expands our notions of what a queer can be: not just fluttery aesthetes with paintbrushes, but also people who rap about band-aids, brown stains, and Smuckers products. Apparently it also means they’ll let him back in England, and it’s about time they realized that those verses about raping and killing Santa Claus were, um, hyperbole. I think. Anyway, behind the gloss and the old-school breakbeats and the radiant b-vox and synth pads and usual musical/arrangement excellence, Igor is a pretty straightforward story about a guy who gets in a relationship with another guy, but that other guy is in the closet, and he eventually ditches the main character for his ex-girlfriend. This is a believable predicament, and one dramatized on pansexual soap operas all the time. Maybe the male love object is indeed behind a mask, and unwilling to defy social expectations in our current climate of fear. Or maybe Tyler smells.

Best Production

FnZ on Denzel Curry’s Zuu. New adventures in bass music, or maybe it’s the same old adventure, only louder. South Florida is renowned for its bottom end, which is appropriate given its geographical position, but this album really takes the cake. Because Denzel is merciful, he doesn’t let FnZ drop it on you all at once. Instead, he boils you slowly like the frog, turning up the low frequency heat, song by song, until you’re absolutely stewing in bass by the end of the set. This is rich, thick, quicksand bass, slippery as Everglades mud. Because the emphasis is on ass, he keeps the rhymes lean and direct and no-frills, and the whole thing whizzes by your chin like a Chinese star, pointed and vicious and traveling with too much force to redirect. I can see this getting very popular, but for practical reasons I hope that it stays regional. A car with subwoofers bumping Zuu could take out every window on this block.

P.F. Rizzuto Award For Best Lyrics Over The Course Of An Album

Billy Woods is as adept at mashing words together as Homeboy Sandman – and that’s saying something – but unlike Sandy, his version of acrobatic wordplay is intentionally mirthless. He gives you punchline after punchline with a heavy emphasis on the punch; he’s sure not smiling when he says any of this. Much of the accompaniment on Hiding Places is as out of tune as a vinyl LP that has warped in a tenement closet, and the cover image is an abandoned house collapsing in on itself. Billy hates you so much he won’t bait a single hook, and over eleven tracks, his resolution becomes its own reward. His intelligence, on the other hand, isn’t something you’ll have to wait for: it’s there from the very first line. Certainly this is not a fun listen, but if you miss that old Definitive Jux doomsday hip-hop sound, Hiding Places is a project worth engaging with.

Best Songwriting and A P.F. Rizzuto Close Second Place

Richard Dawson’s 2020. There has to be something more to life than killing yourself to survive, says Richard Dawson’s narrator on “Fulfillment Center”, one in a set of brutal protest songs sung on behalf of the information age proletariat. The narrator urinates in a bottle because the company (Amazon, surely) won’t countenance breaks, and when a non-native speaker breaks down and starts raving on the factory floor, nobody flinches. They just wait for him to be carted away by corporate security. Then there’s the song about the U.F.O. sighting, and the one sung from the perspective of an anxiety-ridden jogger, and the tale told by the kid who screws up the soccer game to the disappointment of his overbearing dad. These brittle folk-rock productions do not cut corners: they just ramble around the Newcastle countryside getting muddy, following paths through the gorse to weird glades. Dawson sings like an alternate-reality Guy Garvey whose psyche and spirit have been broken to pieces by twenty years sans promotion in the accounts-receivable department. Obviously, this is getting understood as a Brexit statement album, but its messages have global applications, I’m afraid. 2020: nowhere to run.

Best Instrumental Solo

Benmont Tench’s classic organ ride on “Heads Gonna Roll”. Also, I’d like to thank the sax players who tried to summon the spirit of the Big Man: James King on “All The Way (Stay)” and Chiemena E. Ukazim on “Bury Me Anywhere Else”. A woozy E Street salute to both of you; get these guys a couple of cookies from Del Ponte’s in Bradley Beach.

Best Concert You Saw

Calliope Musicals at FM in Jersey City.

Album That Turned Out To Be A Heck Of A Lot Better Than You Initially Thought It Was

Duo Duo by Operator Music Band. Oops, I forgot to write about this one two days ago. Just like they forgot to write much original music, choosing instead to borrow it all from Talking Heads/Stereolab/LCD. But hey, James Murphy is a thief lord, too, and I don’t hear anybody grousing. When these pop Fagins pick a pocket or two, it’s all about the finesse, and more than half of this is really skilled – groovy, bouncy, good communication between pilot and co-pilot, quality signals transmitted over an extremely narrow band. So this is a situational play, tasty when applicable, like Uncle Boons or the squeeze bunt. Me, I like the one that goes ba da da da ba da da da for measure after static measure until the chord changes, at which point it still goes ba da da da ba da da da. Joe Mount would understand.

Also A Grower, But Let’s Not Get Carried Away Here

JPEGMafia’s All My Heroes Are Cornballs. Anything that could be said in defense of vaporwave – its social and conceptual significance, its intervention in the artifice of popular culture – can also be said about hip-hop. Vaporwave sounds like an adjunct professor chopping up elevator music and 8-bit video games to make a point about art; hip-hop is, you know, art. Given the continuity between the styles (if you want to so dignify vaporwave by calling it a style), it was inevitable that somebody like JPEGMafia would emerge from a cloud of pixel dust and start rhyming, and pretty damned well, about memes. I’ve seen this compared to Death Grips, but it’s really more like a bug-fixed Kid Cudi with a bigger chord vocabulary and a wider field of reference, or Childish Gambino plus actual musical talent. Like other projects that take the Internet as a subject, archness and emotional estrangement is part of the message. The heat, when it comes, is largely theoretical – metacommentary about expectations for African-American vocalists, anger as a type of performance, etc. And sometimes he just raps. Those, you’ll notice, are the best times.

Best Arrangements

The return of the Mick on Days Of The Bagnold Summer. And Mick Cooke isn’t just here to toot his horn and do arrangements – he’s back with the six-man (plus Sarah) crew to revive the wispy, twee spirit of the Storytelling era. 2000-02 is the blurriest part of the Belle & Sebastian timeline: that low-energy period when Isobel was getting ready to jump ship, and Stuart David was out, and Bobby wasn’t yet in. Everything was in flux, and you could hear that in the music, which sounded noncommittal, vague, and pretty, like a girl holding her breath, half-shutting her eyes, and groping her way through a grey day. Anyway, the new set is a big blast of nostalgia from a group that doesn’t take backward steps very often, and it puts Stuart Murdoch in an odd position: just when it seemed like he was settling into soporific, neatly-appointed, middle-aged domesticity, circumstances have conspired to make him sing “I Know Where The Summer Goes” and relive his dissipated youth. So does he, ah, still write them like he used to? Well, if by “used to” we mean Life Pursuit or God Help The Girl, which “Sister Buddha” coulda slotted into, the answer is yeah, sure, sometimes. But some of these tunes are dangerously unsupported by the chords. Consider the cheap bossa nova arrangement and overall compositional slackness of “This Letter”, and then consider “Get Me Away From Here, I’m Dying”, with its impeccable circle-of-sharps-and-flats melody that just keeps twirling and twirling like an goddamned elf, skipping across the Clyde on polished footstones. The juxtaposition of the two is a little hard to deal with, even if it doesn’t seem to be hurting Stuart’s feelings or wounding his confidence. Regardless of the context, it’s nice to hear Mick blow his horn again.

Band Of The Year

Charly Bliss

Best Guest Appearance

Lyle Lovett on Rodney Crowell’s Texas. I brought up total depravity in the Sego paragraph, and since this is a concept some struggle with, I wanted to take this moment to stretch out and explain its salience to rock, and hip-hop, and R&B, and blues, and all other forms of art derived from the African American church.

Paul of Tarsus’s letter to the Romans contains the kernel of Christian theology and sociopolitical thought, and it goes like this: you are fucked up beyond recovery, and you require divine intercession. You cannot “good deed” your way out of this spiritual sickness of yours, because only through faith can a man be justified. In Paul’s view, god sends you the law precisely because he knows damn well you can’t live up to it, and he’d like you to come to consciousness of this so you’ll realize you need saving. The law consists of stuff that you know in your bones is right, but which you’re powerless not to do; i.e., you know it’s wrong to covet thy neighbor’s wife, but you’re still going to do it, that and a million other all-too-human things expressly or implicitly prohibited by scriptural codes.

The good news is that you don’t have to be punished for this: Jesus has paid the price for your sin on the cross, and taken a holy beating so that ye may live. All you have to do is believe. If you do believe, your heart will open, and you will receive the gift of grace, and through that gift you will be born a new person in Christ. Easy peasy, right? So simple that it only took the Western church fifteen hundred years to fathom the implications of Paul’s words, and when they did, what they came up with was so draconian that we still recoil from it.

Followers of John Calvin in Geneva (and sometimes John Calvin himself) took the theology of Romans to its logical conclusion, and declared that man was totally depraved — so much so that even if god were to tap him on the shoulder and offer him a gift of grace and a plate of cookies and milk, he’d be too far gone to accept it. There is absolutely nothing he can do to aid his salvation. God’s irresistible grace is his only hope. That grace does not fall on humanity evenly: some people (the elect) will get it, and others (the preterite, or less politely, the damned) will not, and that’s that. The die is cast; the decision on the fate of your disgusting heart and filthy soul was made before you were born.

Now you do not have to be Neil Peart to realize that this view of our spiritual condition is incompatible with egalitarian democracy. Luckily, not too far away in Holland, just as the modern subject was getting hammered out in the shadow of the stock exchange and the tall ships, and painted in all her interiority by Rembrandt and his frenemies, another theologian was coming up with another eirenicist approach. (Eirenicism is the technical term for the use of reason to reconcile mankind with God.) Jacob Arminius is not as famous as John Calvin, and… well, I wish I knew why. It’s probably because Arminian sounds like “Armenian”, which is a completely different thing.

Arminius – and this is crucially important for rock and rap and all the rest of it – completely accepted the Calvinist doctrine of total depravity. He agreed: the human race was about as low as you could go. Where he differed from Calvin was his view of irresistible grace. As he saw it, God’s grace could be resisted: if you really wanted to clam up your ears and dance with the devil, that option was open to you, even if the big guy was calling your name. It followed that the inverse was also true. No matter how degraded your morals are, you’ve got an opportunity to open yourself up to God and let grace do its work on you. Divine grace, he believed, was so powerful that it punches through the total depravity of mankind and creates a kind of caesura in the celestial music. This force – which he called prevenient grace – was available to everybody, in perpetuity throughout the universe. There would be pivotal moments in a man’s life when he would either opt to humble himself before God and let the light in, or turn all the switches off and persist in sin. This was the arc of the cosmic drama: not great deeds, but the private struggle for salvation in which each soul was a separate battlefield.

Calvinists deemed this both illogical and an affront to the concept of divine omnipotence, and convened a synod to declare Arminian theology heretical. and so they did. The Remonstrants – that was Arminius’s party – were soon on the ropes. But while the idea of predestination has never been fully expunged from the Western Christian imagination, Arminius has gotten the last laugh and then some. Arminian theology underpinned the Baptist and Methodist movements in the UK, and, in turn, the African-American Baptist and Methodist congregations that catered to men and women in bondage. From these churches would come a great outpouring of gospel, and soul, and rhythm music indebted to Africa and the islands.

This became a gift to a society that didn’t exactly deserve it: art as an expression of prevenient grace, low-down people in touch with their depravity but with eyes on the sky, anguished cries for help and supernatural sympathy (the blues, brother), and a deep understanding that we’re all in this shitshow together. No elect, no good guys, just the same salvation tearing the fabric of dull reality for those who can get with the vibe. Sin and pain, dirt and redemption, holy fire and the flames of hell: it’s right there, in the way Aretha Franklin pounded the keys, and the way Elvis Costello hits those high notes on “Home Is Anywhere You Hang Your Head”, and the growl of James Jamerson’s bass and the firm crack of Charlie Watts’s snare, and Lauryn Hill’s rhymes and Angus Young’s leads and Nick Drake’s thrumming Martin. If I don’t hear total depravity in your song, buddy, you’re not just doing it wrong – you’re wasting the gift.

Rodney Crowell is an old dude – he’s probably well on the far side of sixty – and any innovations he had to contribute to Texas country music happened in the Eighties. Yet Rodney’s familiarity with total depravity gives him a leg up over younger Nashville artists who are more comfortable with platitudes and pat morality. He knows what’s deep in the heart of uncertain Texas, and maybe even what makes it so uncertain, and he can approach it with the wry irony that only those who’ve fathomed the depths of their own abjectitude can. Willie Nelson and Billy F Gibbons recognize; Lyle Lovett does, too. The song with Lyle is outstanding, so even if you’re going to ignore this one, you might want to drop the imaginary needle there and let it tarry awhile, or just add it to your non-chill playlist.

Whew, okay, that’s enough for today. Thank you for attending services. Theresa will be passing around the collection plate shortly.