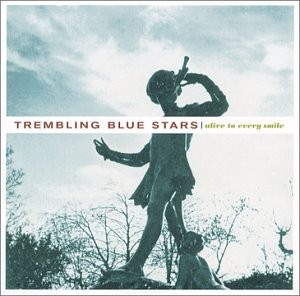

Title: Alive To Every Smile

Year: 2001

Format: Ten song LP.

From: London. That’s rainy suburban London, mind you — the London where the architecture is monotonously pretty, and a double-decker bus splashes muddy water all over your trousers.

Genre/style: There’s good reason to call Trembling Blue Stars a tweepop band, and foremost among them is the reverence in which the band is held by the twee and heartbroken. If you yourself are an indiepop fan who has been dumped by a girlfriend or boyfriend and now suffer from the pains of unrequited love (not to mention being pure at heart), it’s a good chance you already have several TBS albums in your collection. If you aren’t, you probably have no idea who I’m writing about today. While the band’s tonal resemblance to the Lucksmiths is minimal, Trembling Blue Stars fits in with twee indiepop because it really can’t be placed anywhere else. This stuff could be confused with Air Supply if you weren’t listening closely, and I suspect the same could be said about many of the most melodramatic indiepop records made in the ’90s and ’00s. Yet many of the best-known tweepop bands get by with slapdash declarations of romantic longing, skeletal arrangements, and questionable chopsmanship. That’s not what Trembling Blue Stars does. Even the Field Mice — that’s the band TBS evolved from — were much better at their instruments than their peers were, and their records were meticulously recorded and produced to a sheen that’s liable to make a punk rock fan gag. So: heartbroken enough to spend album after album dwelling on it, but not too distraught not to obsess over the drum and synthesizer sounds. Just like Air Supply.

Key contributors: The main perpetrator here is Robert Wratten, who is kind of a test case: just how lovelorn can a songwriter be? How long can a band sustain the same even, doleful, wrist-slitting tone? Wratten is to mournful heartbreak as Wiz Khalifa is to marijuana. Better yet, Wratten is to heartbreak as the Insane Clown Posse is to Faygo: like a juggalo of sadness, he sprays the stuff all over you. You don’t come to this music to dodge what he’s got. You come to be showered in it. Camera Obscura once called an indiepop album My Maudlin Career, and this would also be a good name for Robert Wratten’s biography. If you’re the type of music listener who is attracted to extremes, you’ll want to check out Trembling Blue Stars just to experience how morose popular music can get. The sage Elton John told you that sad songs say so much; Wratten is the man who proved him indisputably right, and kept on proving him right until everybody cried uncle. He turned on the tap in 1987, and whether he’s called the project Northern Picture Library, The Field Mice, Trembling Blue Stars, or one of the other names he’s used, it’s always been the same. He’s fixed his stories of romantic desperation to six-string shimmer, sweep synthesizer pads, and occasional techno beats, and sung it all in the stupefied but unsurprised mumble of a chess club president who’d just seen his former girlfriend in the arms of the football captain. Other Trembling Blue Stars albums cut Wratten’s misery with female vocals mixed to emphasize the woman’s unattainability; Aberdeen’s Beth Arzy and Annemari Davies (who we’ll get to shortly) both sweeten Alive To Every Smile a bit, but more than anything else in a pretty big catalog, this one is the bandleader’s show. The other major force on this record is producer Ian Catt, who is probably best known for his work with St. Etienne, an electropop act that has never been properly appreciated in the States. Catt has fitted Wratten with various shades of melancholy since the days of the Field Mice. Occasionally he’s been accused of overproduction, as if the whole purpose of his job wasn’t to get everything to shimmer, swoon, and ache by all means (and by all overdubs) necessary. Lucky for Wratten, Catt is a shimmer, swoon, and ache specialist, and he’s never let his pal down. That means that Trembling Blue Stars albums rise and fall on the strength of Wratten’s writing, and his ability to sustain and focus his peculiar vision.

Who put this out? Sub Pop. By 2001, the label had more or less completed its transition from an outfit that backed the likes of the Screaming Trees to an outfit that backed the likes of the Shins. Still, memories of Kurt Cobain howling from the muddy banks of the Wishkah don’t fade so easily, and TBS’s jump to Sub Pop at the turn of the millennium was accompanied by a mild jolt of cognitive dissonance. (St. Etienne made a similar leap from an indiepop label to Sub Pop around the same time.) Broken By Whispers, the Trembling Blue Stars album that preceded Alive To Every Smile, was the first Wratten project to be released through Sub Pop, and I recall it got a pretty nice push from the imprint. For a shining afternoon, it seemed possible that TBS could gain the same sort of foothold in the States that Belle & Sebastian had. Back home in the U.K., Wratten was still working with Shinkansen, the successor label to Sarah Records, a quasi-legendary operation that put out albums that sounded exactly like what you’d expect to get from a label called Sarah Records. Picture a girl named Sarah with a hair clip and a bicycle with a bell and a basket, and a tear-stained love letter in the front pocket of an argyle sweater. Go on, give her an ice cream cone for good measure. The Field Mice are sometimes described as the quintessential Sarah act, yet Wratten’s understanding of classic pop architecture set the band apart from the very beginning. Those interested in further study might make an investment in Where’d You Learn To Kiss That Way?, an exhaustive compilation that inspired ten thousand cupcake pop bands, at least fifty of which I played synthesizers for.

What had happened to the act before the release of this set? The Field Mice were followed by the slightly more electronic Northern Picture Library, followed by the slightly less electronic first Trembling Blue Stars album, followed by the slightly more electronic second Trembling Blue Stars album, followed by the slightly less electronic third Trembling Blue Stars album. To complain that these records all sound the same is to miss the point utterly. It’s monomania that Wratten is chronicling. He required an aesthetic to match his obsession. The early history of Trembling Blue Stars is one run-on journal entry that begins in a blue funk and descends further into despondency from there. The first album is a clutch of fresh breakup songs, and they’re redolent with not-so-secret fresh breakup hope: somehow the tectonic plates will reverse and the dawn will break and the girl will come running back with mascara a little smudged from weeping but no worse for the wear. By the time of Broken By Whispers, Wratten’s faith was shot to pieces, and he’d arrived at the conclusion that even if he managed to land the girl he was fixated on, she’d changed so much since the breakup that the rekindled relationship would be worthless. “The person you were, I know you’re not her, she’s gone away,” he sighs on “She Just Couldn’t Stay.” All is lost, all is shitty, nothing on the horizon but the dreary procession of loveless days. The one-two gutpunch of “Sleep” and “Dark Eyes” that concludes Whispers could be the most depressing ten minutes in the history of recorded music. Here Wratten has resigned himself to a life of misery and meaninglessness; the breakup he still can’t make sense of has put a hole in the hull, and the ship is destined to limp around a torpid sea until it finally goes down. In its fatalism, many wounded indiepop kids found this romantic. Some of us, God help us, even found it sexy.

What obstructions to appreciation did this album face? This brings us to the one leading fact that even casual fans know about Trembling Blue Stars: Robert Wratten wrote many, and quite possibly all, of these confessional, excoriating, self-pitying early songs about his bandmate Annemari Davies. TBS was initially designed as a vehicle for Wratten to express his devastation about the breakup. In case there was any ambiguity, he put a picture of Davies on the cover of the second album. What’s remarkable about this is that for the first two albums at least, Davies remained in the band, and continued contributing to Trembling Blue Stars until the very end of the project. (Those must have been some rehearsals.) If this had happened between, say, Beyonce and Jay Z, there’d be an industry devoted to unpacking the nuances and dynamics of the lyrics; since it’s indiepop, we’ve got to satisfy ourselves with occasional weblog posts. Davies does not seem like the sort who kisses and tells, and interest in the vagaries of Wratten’s romantic life has waned, so we’ve got the albums to go on, and that’s about it. In any event, there’s something deeply sadomasochistic about this arrangement — although even at the time it was hard to tell who the masochist was. It is instructive to know that as twee as the handle sounds, “trembling blue stars” is actually a phrase pinched from The Story of O. To indiepop fans nursing their own wounds and resentments, it was something of a relief to realize that no matter how pathetic they felt about their own love lives, Wratten was willing to be even more pathetic, and in public. Here was a man who didn’t even have the stones to throw the girl who’d dumped him out of his band. As good a songwriter and wordsmith as he is — and he is — it is indisputable that Trembling Blue Stars owed much of its prominence within indiepop to the soap opera at the heart of the project. Wratten, a calculating musician, was willing to capitalize on his own emotionally dysfunctional life story. Yet by the time of Alive To Every Smile, this had become something of a problem. Never mind that there was nowhere to go after the desolation of “Sleep” and “Dark Eyes;” he was beginning to be known as the guy who couldn’t stop writing about getting dumped. Now, as pop brands go, that’s a pretty good one, but like all pop brands, it’s confining. Since there’s not much sonic differentiation between TBS album, it was easy to assume that Alive To Every Smile was more of the same. Just about every reviewer jumped to the not-unreasonable conclusion that Sad Man Wratten was at it again. Only he wasn’t; not really. Because unless there’s a dimension to the Davies story that he hasn’t chosen to overshare, this time around, he’s writing about somebody else.

What makes the words on this album notable? Right off the bat, Wratten signaled that this was going to be a different trip. “Under Lock And Key”, the kickoff song, opens like this: “You’ve got to stop fucking her up, you’ve got to grow up.” Let’s examine both halves of this uncharacteristically profane (by Trembling Blue Stars standards) note to self. Wratten hadn’t ever been too concerned with growing up before, and that’s because he presented his heartbreak as an apocalypse that had forever halted the hands of the clock. Yet here he was hinting that he knew there was something adolescent about the position he’d taken on the first three Trembling Blue Stars albums — and in Northern Picture Library and the Field Mice, too. I hope you realize that I’m not being pejorative in any way by calling Wratten juvenile. If my girlfriend were to dump me, I’d throw a tantrum so whiny and immature that every DYFS agent in town would be forced to storm my house. Even if I’ve never lived through the unpleasant things Wratten sings about on Her Handwriting, I can sympathize with the extent of his meltdown. Sometimes the only justifiable reaction is a toddler’s reaction, and there’s no sense in dressing it up in sophisticated b.s.; that’s why “Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want”, as laughable as it is, goes straight to our souls. Anyway, that’s not the Robert Wratten we’re getting here. We’re getting a version of Wratten who understands that the meter is running, and that love affairs are pierced through the core by time’s arrow along with everything else. With it comes another realization: the narrator is just as responsible for the turmoil as the object of his affection is. On Alive To Every Smile, Wratten plays the perpetrator, not the victim. He’s no less soft-spoken than he ever was, but now he’s unashamed to admit that he’s as driven by the sexual imperative as any frathouse mook: “I wanted her so bad, you see,” he explains, flat-footedly, on the album’s centerpiece, “I just wouldn’t stop at anything”. Desire, on Alive To Every Smile, is a force that prompts people to behave impetuously and irresponsibly, and the more Wratten’s protagonist tells himself he’s doing wrong, the harder it becomes for him to locate his virtue. The woman he’s after is probably married, certainly off-limits, and tempted to play with fire. The main character begins the story as a would-be tweepop lothario interrogating his own morally compromised position, plunges into the deep end of the pool anyway, and discovers the water is a lot hotter than he expected it to be. By the end of the album, she’s taking the train back to the life she knows, and he’s the disbelieving, heartbroken schmuck on the platform talking to himself. So, yes, the result isn’t so far removed from what you’d get on other Trembling Blue Stars projects. The crucial difference is that this time Wratten knows that he’s been an active participant in his own emotional demolition. This is a grownup’s realization, Alive To Every Smile is a grownup story, and as every grownup knows, but every pop song attempts to mystify, an affair is always a tragedy. In order to make the ultimate album about what it’s like to be in the midst of one — because that’s what we’ve got here — it takes an experienced tragedian, one painfully familiar with the dynamics of self-deception. “I think love should come with madness,” sings Wratten on “Maybe After All,” and this preference stands as an implicit critique of the girl he’s chosen to seduce: she’s not going to go utterly crazy with him and sacrifice everything, and he knows it, but he’s already gathered too much momentum to stop himself from going over the edge of the cliff. “When we see a chance to be loved,” he sings on “With Every Story” in a prompt that sums up all of his work, but especially this album, “who knows what we’re capable of?” Now, Robert Wratten’s lyrics are often called diaristic, and it’s possible that Alive To Every Smile is just as autobiographical as the first three TBS albums. He may have actually picked up and fallen for a married woman, she may have refused to ditch her husband, and this set may be at least as epistolary as Here, My Dear. Those still interested in Wratten’s personal story will no doubt notice that the writer has appended a mysterious set of initials to the lyrics printed in the CD booklet. Me, I think it’s more significant that Wratten chose to include printed lyrics in the first place. This is the only Trembling Blue Stars album that comes with the poetry attached, and I do not believe that this is just the residue of Sub Pop’s art design department. Wratten is particularly proud of this set, and he wants to make sure you notice how succinct and epigrammatic they are, how economically the story is advanced, and how each image has been carefully seared into the lines to reinforce the narrator’s move from ambivalence to rhapsodic abandon to destabilization to stupefaction. “It’s the rest of our lives — that’s all we’re making a difference to!,” he sings on “Ammunition,” in a typically sympathetic but histrionic closing argument. Apparently she’s unmoved. Or, more likely, her idea of the value of the rest of her life differs sharply from his, and she’s calculated that she’s got more to lose than he does. He believes surviving isn’t everything; she doesn’t want to be drowned. Tough luck, Bobby.

What makes the music on this album notable? It was the canny Tim Benton of Baxendale who, on “Music For Girls,” implicitly called for solidarity between fans of lovelorn tweepop, delicate dance music, and every other form of art that the chavs can’t stand. Since we’re all facing the same beatdown from the same fraternity brother on the same cultural playground, a missing link between Belle & Sebastian and the Pet Shop Boys shouldn’t be that difficult to find, right? Benton wanted Baxendale to be that missing link; Ian Catt probably felt the same way about St. Etienne. Trouble is, no matter what Robert Smith and Bernard Sumner were able to accomplish in the ’80s, it is brutally hard to mope and dance at the same time. Brood and dance, maybe, or indulge in glorious self-pity while kicking at the pricks. But true heartrending tweepop has little relationship to the booty. (Please oh please be a pal and don’t bring up “Stillness Is The Move”.) Ironically, Robert Wratten, King Mouse himself, is the practitioner who’s come the closest to a genuine fusion. Some of this is probably accidental; while he’s got his heart in the house music experiments on the Lips That Taste Of Tears album, I think they’re there to evoke the psychic destabilization of the disco and, only distantly after that, to get you to shake it. Since it’s basically a concept set about putting trouble where there wasn’t any, Alive To Every Smile steps back a bit from the dancefloor and privileges mood over motion. There are more achingly slooooooow Christopher Cross ballads here than Wratten usually foists on his listeners, which is not to say that they aren’t really good Christopher Cross ballads. The exception is the slightest song on the set, and the only one that doesn’t really advance the story — “St. Paul’s Cathedral at Night,” a reverie with a comedown-phase techno pulse and a breathy vocal sample. Like “ABBA on the Jukebox,” an earlier song, “St. Paul’s” consists of Wratten flagellating himself with strands of memory; thus, the music needs to simultaneously sting and feel dreamlike. He pulls it off, but the ambience comes at the cost of the album’s forward momentum. Other experiments work better. Album closer “Little Gunshots” is semi-bossa nova, which ought to be a farce but works brilliantly instead by sucking every breath of equatorial breeze from its dessicated version of tropicalia. “Here All Day” extends Wratten’s fascination with fatalistic early-’60s pop ballads; “Under Lock And Key” sets the tone with mildly distorted drums and guitar and a marginally rougher vocal approach than anything TBS had yet attempted. It all serves to anticipate, echo, offset, or frame Wratten’s Fifth Symphony: “The Ghost Of An Unkissed Kiss.” Here is the maestro of lovelorn excess in rosy overdrive, layering guitar track upon guitar track (natch, one is even backward), saturating the frequency spectrum with organ, synth, and backing vox, mixing machine beats with live drums, and letting the whole shebang run for four-and-a-half minutes of indiepop glory. In case one melodic hook wasn’t sufficient, Wratten baits the fly-trap with a second, and then a third, and then a fourth, with each one steady enough to support a song on its own. The composition couldn’t be any more assured, but the motivation is frantic: if Wratten can just make the song catchy enough, irresistible enough, the girl will get tangled up in it like a kitten in a ball of yarn, and he wouldn’t ever have to say goodbye again. In years of playing indiepop, I’ve never seen it work out that way, but our best songwriters go right on trying. As romantic fallacies go, it’s one of the most fruitful.

Dealbreakers? Wratten’s voice is something of an office-worker grumble, and it can sound downright comical when paired with the gigantic arrangements of songs like “Unkissed Kiss.” No matter what the band does, or how many glossy six-string and backing vocal tracks he overdubs, he always sounds like a sad sack, and you may occasionally tempted to slap some sense, or some animation, into him. (This said, Leonard Cohen has gotten away with the same thing for decades.) On other albums, Davies and Arzy brighten things up with lead vocals of their own, but this one is his narrative masterpiece, and he holds center stage for nearly an hour, only breaking the soliloquy for long sections of guitar wash. If you haven’t warmed up to him by the fourth song, there’s a good chance this isn’t for you. I am also aware that there are those who still believe male pop singers ought to behave on record like Sylvester Stallone in Cobra, and others who are moved to write thinkpieces about the bothersome sociocultural implications of the twee aesthetic, and others with a reasonable distaste for the act of kissing and telling. If you fall into one of these categories, you will certainly pitch Alive To Every Smile out the window. Pop-rock did get rather wimpy and passive-aggressive in the ’00s, and there certainly is a time and a place for Motorhead. But if you want to argue, and some do, that Robert Wratten’s beleaguered, poetic diary entries constitute illegitimate rock practice, I can’t hang with you there. Heartbreak is as essential subject for American popular songwriters as Cadillacs and blue balls. As Fleetwood Mac, or Kanye West, might tell you, if you’re going to indulge yourself, you may as well take it to the limit.

What happened to the act after this? Wratten followed up Alive To Every Smile with the only dud in his discography: The Seven Autumn Flowers, which wasted a great TBS handle and a beautiful cover image on soporific, unmotivated, second-rate material. The exception is the terrific lead single “Helen Reddy,” sung by Arzy, which is probably about the same affair that consumed Wratten on the prior set. Seven Autumn Flowers would be the last Wratten project to get a decent, albeit indie-sized, push in the States (it was released by Hoboken’s own Bar/None); its failure to expand the Trembling Blue Stars audience probably threw the last shovelful of dirt on Smile. In America at least, tweepop moved on to other heroes, and it seemed likely that we wouldn’t be getting any more installments of the Adventures of Robert Wratten. As it turned out, the old fox had one last trick to play. The Last Holy Writer, released in 2007, broadened the arrangements, varied the tempos and the beats, and let a few rays peek through the clouds. A few songs were, in longstanding indiepop tradition, gay-affirmative; “A Statue to Wilde,” the seven-minute closer, manages to be gorgeous and also make a political statement, and if you think that’s easy, try to come up with another song you can say the same thing about. The presence of topical verse demonstrates that Wratten had stepped out of the confessional, at least momentarily — and when he does sing about himself, as on “November Starlings,” he’s provisionally content. He remains willing to put a chorus like this one, from “Idyllwild,” in Arzy’s mouth: “Life was so open then/now it’s closing in/one by one our dreams have disappeared.” Yet for the first time, it seems possible that Wratten is singing about another character, and that means a substantial difference in tone. Trembling Blue Stars retired from live performance after briefly supporting Holy Writer; Fast Trains And Telegraph Wires (is Wratten good at titles or what?) followed, almost as an afterthought, a few years later. It’s a good album and a fine end-note, but it played like a reiteration of past glories. In America, it sunk without a ripple.

Will this album ever receive its propers? Tweepop posterity, lusting after youth in strict conformity with the stereotype, tends to overrate the Field Mice and underrate Trembling Blue Stars. That’s when people are thinking of Robert Wratten at all, which happens all too infrequently. The grand, glossy arrangements that he and Catt favored have gone out of style; the Pains of Being Pure At Heart — an obvious bunch of Wratten fans — are more inclined to run their mixes through nasty-ass distortion. Consider that the latest Pains album has been slated because Kip Berman has cleaned up the sound and made something not unlike a mid-’90s TBS set, and you begin to realize the problems that the Wratten revival faces. The Field Mice stand to be rediscovered first, and with it the story of Sarah Records and the doomed Wratten-Davies romance. Thus, even if Americans get hip to Robert Wratten in the future — not at all a likely thing — Alive to Every Smile is likely to get lost in the shuffle. Wratten probably won’t be able to call attention to his narrative masterpiece without getting back on the road and playing songs from it — preferably “Ghost of an Unkissed Kiss,” but “Little Gunshots” and “Under Lock and Key” are likely to intrigue pop fans, too. Luckily, Wratten appears to have unretired again: there’s a Facebook page for a new project called Lightning in a Twilight Hour, which I can’t believe wasn’t already the name of a Trembling Blue Stars song. I’ll be the first in line at the record store, if there were still record stores that stocked this stuff, or if there were still record stores, which there hardly are, but you know what I mean.

Tris McCall: tris@trismccall.net